The Evanston Steps in the Fremont neighborhood, leading to the Burke-Gilman Trail and providing a good view of boat traffic on the ship canal. Photo by Valarie, August 2025.

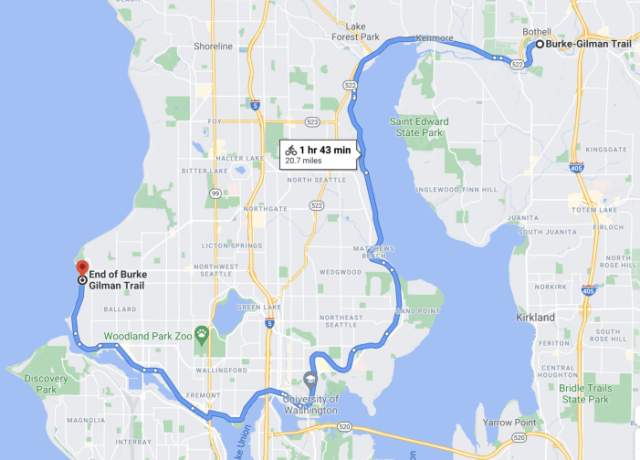

One of Seattle’s amenities is a trail which traverses the city and extends to the east side of Lake Washington. Sometimes called “Seattle’s longest park,” the trail is overseen by the Parks Department and serves those who walk, run, or travel by bicycle for exercise or to commute to work.

In the 1970s the name “Burke-Gilman Trail” was given to this former rail line when a group of Wedgwood neighbors advocated for its conversion to a trail. In another article on this blog I have told the story of how the committee came up with the Burke-Gilman Trail idea.

The members of that 1970s citizen-activist group suggested that the names of Thomas Burke & Daniel Gilman be given to the trail, because in the 1880s these men were the key movers-and-shakers in the creation of Seattle’s own railroad, called the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern. In this blog article I will explore some of the reasons why these men, Burke & Gilman, came to Seattle, what their lives in Seattle were like, and the legacy they left.

The Burke-Gilman Trail proceeds along the north shore of Lake Union and over to Lake Washington to the east.

Thomas Burke: from Michigan to Seattle

Thomas Burke (1849-1925) was born in New York State of an Irish immigrant father. The Burkes moved to Iowa where Thomas first began to try to contribute financially to his family and get more education. At the age of eleven he went to live with the owner of a grocery store, where Thomas could attend school in town and work the rest of each day as a store clerk.

As a teenager, Thomas moved to Michigan where there was a school he could attend while living on a neighboring farm and helping with the farmwork. When he turned eighteen Burke earned money by teaching school for part of the year, and he attended university at Ann Arbor. He did not graduate but instead went to “read law” in the office of a practicing attorney until he was able to pass the bar exam to become an attorney himself.

Many of Seattle’s early white settlers seemed to come out of nowhere, boldly joining in with the civic activism of what was then a very small settlement. Records of Thomas Burke’s background said that he received a letter from someone he had known in Michigan, who had come to Seattle and told of opportunities for growth in the Pacific Northwest. Burke left Michigan and arrived in Seattle on May 3, 1875, at age 25.

In the 1870s there were constant rumors of the prosperity which would be generated when railroads reached the West Coast. Conversely, when railroads bypassed a place, the population fell. Thomas Burke had already experienced this where he had been living and practicing law in Marshall, Michigan. The nearby cities of Battle Creek and Jackson, Michigan, had a rail line and Marshall did not.

Seattle’s campaign for a railroad

Arriving in Seattle in 1875, Thomas Burke found the city still trying to recover from the huge shock of having the Northern Pacific Railway choose Tacoma as their transcontinental terminus in 1873, instead of Seattle. Burke found employment in the law office of John Jay McGilvra, and over the next ten years they worked on plans to overcome the legal and financial problems of getting a rail line for Seattle.

Over the course of his career, Thomas Burke had other law partners but he’d formed an unbreakable bond with the McGilvra family by marrying Judge McGilvra’s daughter Caroline in 1879.

John J. McGilvra (1827-1903) was a contemporary of Abraham Lincoln’s as they had known one another in Illinois. In 1861, after being elected president, Lincoln appointed McGilvra to be the U.S. Attorney in Washington Territory. The judicial district included all the counties from Seattle to the north and west, including the San Juan Islands, the Olympic Peninsula and up to Whatcom County bordering Canada.

Sometimes cases would be brought to trial in Seattle but more often the court “rode circuit,” traveling by boat to outlying communities. Judge McGilvra hated this kind of travel so he settled in Seattle and had Burke, as his junior law partner, take many cases. Along with gaining legal experience, in his travels on the trial circuit Burke gained an overview of the resources and economics of the Puget Sound region.

Burke’s economic investments and civic activism

It has jokingly been said that people who came to Seattle seemed to soon give up their original vocations and instead, in Seattle they became real estate investors. McGilvra & Burke did not give up the practice of law, but they certainly had many other sidelines including investment in real estate and property development, sites of raw materials like coal, and promotion of transportation systems such as streetcar lines.

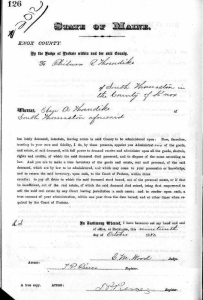

Burke was elected county judge of probate in 1876, and ever after he was always referred to as Judge Burke. “Judge” of probate did not necessarily involve disputes or court hearings but was meant to monitor the distribution of a deceased person’s assets. The judge of probate was to give oversight so that debts were paid and any remaining assets were distributed according to the will which the person had filed.

Burke’s experience with the probate process benefited his legal knowledge in general and it came into play in accomplishing the Seattle settlers’ long-time desires: creating a canal from Lake Union out to Puget Sound and creating a railroad line to run east of Seattle to areas of resources such as timber and coal. Acquiring property for the future canal and the rail line, had to do with the inheritance issues of landowners.

The Seattle economy was an “extractive” one, dependent upon getting timber and coal to the downtown waterfront for sending out via ship. Cars & trucks had not yet been invented, and Seattle still didn’t have a railroad, so the only way to move these heavy products was over the water. As early as 1854, Seattle’s first white settlers had seen that it would be possible to create a canal from Lake Washington to Lake Union and on out to Puget Sound so that ships could make the journey, carrying timber and coal. But heavy equipment such as excavators had not yet been invented, so in the 1880s some efforts were made by hand-digging to widen and deepen an existing stream, a slow and arduous process.

Seattle historian Richard C. Berner wrote that:

“Before the 1890s, a number of civic leaders, including Arthur Denny, Governor John H. McGraw, Judge Burke, Burke’s father-in-law John Jay McGilvra, along with several real estate speculators and settlers north of Shilshole Bay, expected to have a canal dug from Lake Washington to Shilshole. Burke and his allies believed that such a waterway would be important to the development of a steel industry they hoped to establish near Kirkland. At the time, Seattle, like Portland and many other cities, aspired to become the “Pittsburgh of the West.” The canal would also provide a route to float raw timber from east of Lake Washington into Puget Sound; it would also mean that coal would no longer have to be barged, and then portaged, from east of the lake to Elliott Bay.” (Seattle 1900-1920, page 17, see source list).

Making way for a ship canal

Boats in the ship canal, bicycles on the Burke-Gilman Trail, looking westward towards Evanston Avenue in the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle. Photo by Valarie, August 31, 2025.

In addition to his efforts to get a railroad for Seattle, Burke was on the committee which sought to create this ship canal. His study of the legalities of the probate process bore fruit in the 1880s when he came up with a plan to resolve the roadblocks to building both a canal and a railroad. The canal and railroad would run parallel to one another along the northern edge of Lake Union, through present-day Fremont, Wallingford and the University District.

An obdurate person, John Ross, had owned land on both sides of the present-day ship canal which was, at first, a small stream called Ross Creek or The Outlet. In the 1880s Ross had been taken to court for obstructing the workers who had been commissioned to widen the stream for the use of boats, which could at least tow logs if not carry them.

John Ross died in May 1886 while the canal and rail line plans were in-progress. The memoir of Ross’s daughter, Ida, told of the visit of Daniel Gilman to their home, to ask the widowed Mrs. Ross for a right-of-way for the railroad which Burke & Gilman were hoping to create.

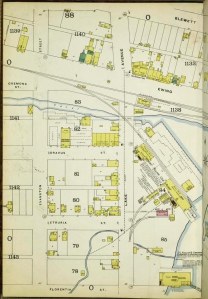

As shown on a fire insurance map of 1893, the Fremont neighborhood was centered around its bridge over a small stream, with a lumber mill on one side.

Next, Judge Burke went to work on a long-unresolved probate problem, dating back before Burke had come to Seattle. As of 1886 the present-day Fremont neighborhood of Seattle was still vacant because of ownership issues. The land had been the 1854 homestead claim of William Strickler. The land claim included the small stream flowing out of Lake Union, which the canal committee hoped to enlarge for passage of ships. The land was centered at the present site of the Fremont Bridge.

William Strickler had disappeared in 1861, and no one ever found out what happened to him. He was presumed dead, but his relatives back in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia never responded as to the disposition of Strickler’s land. Finally, Judge Burke brought the case to court for non-payment of property taxes. The land was sold at auction but with a section set aside for the canal and the railroad.

Judge Thomas Burke spent the rest of his life in Seattle and was involved in every aspect of development. He participated in the legal and legislative work which was needed, to finally bring the ship canal plan to fruition in 1911-1917.

In contrast to Burke’s life-long stay in Seattle, his SLS&E co-developer, Daniel Gilman, was only in Seattle for a short time, though he retained investments around the Seattle area.

Daniel Gilman

Daniel Hunt Gilman (1845-1913) arrived in Seattle in 1883 at age 38. He had a background of multiple areas of expertise. He’d turned 18 during the Civil War and had served with a Maine unit in 1863-1864. We know that many Civil War veterans saw trains for the first time during the war, and they began to realize the vital importance of this transportation network.

After the war Gilman lived in New York City, working in commerce and engaging in real estate speculation. At age 32 in 1877 he graduated from Columbia Law School and practiced law until he went to Seattle in 1883.

Since Daniel Gilman was a practicing attorney, he established himself in Seattle while getting to know people and getting involved in issues. He was part of the group which incorporated in 1885 as the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railroad. Gilman’s role then became fundraiser, and he made a series of trips to Eastern cities, including New York City where he had formerly lived, to engage investors in Seattle’s railroad project.

Daniel Gilman was born in Maine, into a very large family. His father Henry Gilman had had six children with his first wife, and after her death he married again and had eleven more children. Daniel Gilman was the fourth son born in the second group of children.

Daniel Gilman’s arrival in Seattle in 1883 seemed sudden, but he may have been hearing about the Pacific Northwest from his older brother, Captain Alvin Mason Gilman. A.M. Gilman had also served in the Civil War and then he became something of an adventurer. He is listed on the census of 1870 as living in the gold-mining area of California.

Daniel Gilman’s arrival in Seattle in 1883 seemed sudden, but he may have been hearing about the Pacific Northwest from his older brother, Captain Alvin Mason Gilman. A.M. Gilman had also served in the Civil War and then he became something of an adventurer. He is listed on the census of 1870 as living in the gold-mining area of California.

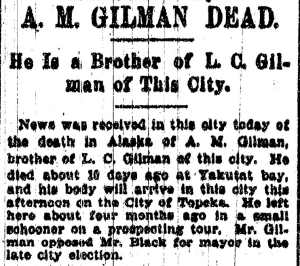

A.M. Gilman became a ship captain based in Seattle. He married in 1883 and became involved in city politics. At age 56 his thirst for adventure awoke again, and he traveled to Alaska during the gold rush. When he died in Alaska in 1896 his death notice in the Seattle newspaper did not mention his brother Daniel Gilman, who was no longer living in Seattle at that time. Mentioned in the death notice of A.M. Gilman was another brother, L.C. Gilman.

Upheaval in early Seattle

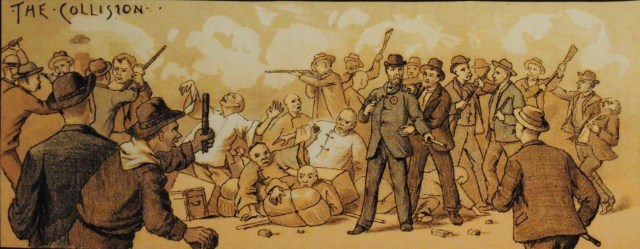

In the 1880s regional labor unrest began to focus on the Chinese to blame them for the unemployment of white workers. In Seattle, there were Chinese laundries and herbal shops, and many “housemen” working for private families.

A little-known anecdote about Daniel Gilman was something which occurred during the anti-Chinese riots on February 8, 1886. At that time Henry Yesler (Seattle’s sawmill owner) and his wife Sarah lived in a house at about where the King County Courthouse is now, at Third & James Streets. Mrs. Yesler noticed crowds and some sort of disturbance to the south, so she sent her Chinese houseman down to the laundry to pick up Mr. Yesler’s clothing. This man returned with another man who was seeking refuge from the rioters and said that Mr. Yesler’s clothing was gone, as the laundry had been looted.

In court testimony recorded in the Daily Intelligencer newspaper later in February 1886, Mrs. Yesler testified that four white men had pursued her Chinese houseman and had demanded that she deliver him over to them. All the Chinese in Seattle were being forced down to a ship on the waterfront as the rioters intended to get them out of town.

The four men said to Mrs. Yesler that if she didn’t send out the Chinese, they would blow up her house. Mrs. Yesler was a person not to be trifled with, so she replied with a shotgun, saying, “go ahead and try it.” At that point Daniel Gilman, seeing what was going on, approached and ordered the rioters to get out of the Yesler’s yard.

On that day the militia (volunteers) was called out, meaning that the disturbance was more than the ordinary police force could handle. In Captain George Kinnear’s account of the events, both Daniel Gilman and his brother L.C. Gilman were listed as members of the Home Guard who were to keep order and prevent the rioters from harming the Chinese.

The Gilman and Thorndyke families from Maine

Daniel Gilman was married at age 42 in 1888, to a girl from Maine whom he met in Seattle. He and the Thorndyke family may not have known one another back in Maine, but Seattle was “a small world” in the 1880s and it would be natural for people to get to know others from their home state.

Like Daniel Gilman, Grace Thorndyke was from a very large family. Her father, Captain Eben Thorndike, was just one of many men from Maine who explored the resources of the Pacific Northwest. In other articles on this blog I have noted the Maine men who established lumber mills in the Pacific Northwest, such as Pope & Talbot, and Marshall Blinn who made sea journeys back and forth from Maine.

Captain Eben Thorndike had bought property in Seattle and after his death in 1880 his wife Rosilla and their remaining unmarried children all moved to Seattle. One of the Thorndyke daughters, Estelle, married Captain William Ballard, namesake of the Ballard neighborhood. Captain Ballard was involved with Burke & Gilman in securing properties for the rail line and for the canal to run east-west along bodies of water including the stream called Ross Creek or The Outlet, and Lake Union.

In Seattle, where there was a shortage of women, the widowed Rosilla Thorndike may have hoped to find husbands for her numerous daughters. Her daughter Delia Thorndyke married John Hatfield, a business associate of Captain William Ballard’s, but tragically both John & Delia Hatfield died before the year 1900. In the 1880s, two Thorndyke daughters, Minnie and Grace, were listed in the Seattle City Directory as schoolteachers and then each married in 1888. Minnie married a Seattle businessman, James Bothwell, and Grace married Daniel Gilman. The only son of the Thorndyke family, George, married in 1896 and spent the rest of his life in Seattle as owner of a shipping company. The youngest member of the Thorndyke family, Alice, married in Seattle in 1899 and moved to California.

Along with Daniel Gilman, another person who married in Seattle in 1888 was his younger brother Luthene Claremont Gilman (1857-1942). L.C. Gilman had come to Seattle in 1884, and like Daniel Gilman, he practiced law while getting involved in civic issues. Although Daniel Gilman had been part of the founding of Seattle’s own SLS&E Railroad, his brother L.C. Gilman later became better known in association with railroads.

In 1892-1893 the SLS&E Railroad was absorbed into the network of the Great Northern Railroad of James J. Hill. L.C. Gilman spent the rest of his life working for Hill’s railroad as a manager.

The outreach of the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railroad

Seattle’s own railroad, the SLS&E, reached as far as Snoqualmie Falls, advertised as a picnic spot, but the main purpose of the line was to carry raw materials from outlying areas into the city. Daniel Gilman bought property around Snoqualmie Falls and surveyed for minerals, as well as investigating for a method of generating electrical power at the falls.

Daniel Gilman invested in coal and iron mining in eastern King County, in a region called Squak. In gratitude for his investment, the citizens renamed the town “Gilman” in 1892. In 1899 the town was renamed again, Issaquah, because the postal service said there was already another Gilman in Washington, and they wanted to avoid confusion.

Another region named for Daniel Gilman was a plat name for house lots in Ballard, where there is still a Gilman Park today.

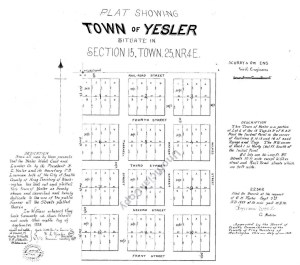

Town of Yesler plat map filed in 1888 by Henry Yesler and his investor, J.D. Lowman. Top line of the map is NE 45th Street just east of the intersection of Union Bay Place NE.

The reason that the SLS&E Railroad had been routed along lake shores, was because of level ground to run on, and for the loading of goods from docks. At the present site of the Laurelhurst neighborhood, a spur line accessed the new Yesler sawmill which had been set up there on Union Bay. It would not have been possible for this sawmill to exist, without the railroad to carry away the products.

Along the western shore of Lake Washington, agricultural produce sent by boat from outlying areas could be unloaded at docks and then loaded onto the train. Thomas Burke, along with co-investors Morgan Carkeek and Corliss P. Stone, set up a brickmaking plant at Pontiac (present site of Magnuson Park on Lake Washington) where finished products could be loaded onto the train. The brick plant was ready to go into production in early 1889, just in time to contribute to the rebuilding of downtown Seattle after the Great Fire of June 6, 1889.

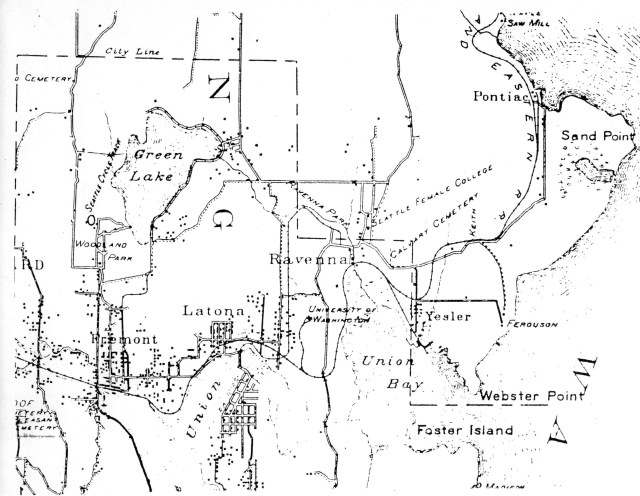

This map of 1894 shows the snaking line of the SLS&E Railroad and the communities along the route. Rail stops averaged one to one-and-a-quarter miles apart.

McKee’s Correct Road Map of Seattle and Vicinity, 1894, shows the railroad line. Courtesy of the Seattle Room, Seattle Public Library. The snaking line of the SLS&E Railroad is shown through the communities of Fremont, Latona (Wallingford), Ravenna, Yesler (Laurelhurst) and north past Sand Point. Block dots indicate population clusters. Calvary Cemetery, established 1889, is a point of reference at the corner of NE 55th Street and 35th Ave NE.

The coming of the Great Northern

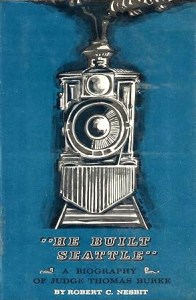

Running a rail line was expensive and by 1892-1893 the operation of the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern was absorbed into the powerful Great Northern Railway Corporation of James J. Hill. Hill well understood Seattle’s burning desire for a transcontinental line, so that raw materials could flow eastward, and manufactured goods could be sent westward to Seattle. The biographer of Judge Thomas Burke wrote that “The selection of Seattle as its western terminus by the Great Northern was possibly the greatest single factor in the city’s growth and subsequent prosperity.” (Page 243, He Built Seattle by Robert C. Nesbit.)

Seattle historian Richard C. Berner wrote that,

“Before James J. Hill’s Great Northern Railroad provided Seattle with its first transcontinental transportation connection in 1893, the city’s economy rested almost entirely on coastal maritime trade in the Puget Sound basin, along the British Columbia coast, and into the fjords and harbors of southeastern Alaska. Logs, lumber, coal, livestock and food products were traded. At the time, Seattle did not have an industrial economy based on manufacturing; the few finished goods produced in the city were, in fact, consumed locally. After the transcontinental railroad line reached Seattle….. Seattle’s commerce experienced an eight-fold expansion between 1895 and 1900.” (Page 10 of Berner’s Seattle 1900-1920, see source list).

Direct access to Seattle via train was a factor in the Yukon Gold Rush of 1897 when thousands of people came to Seattle as a jumping-off place to the gold fields. Seattle’s population exploded with growth of commercial sites to serve the gold rush traffic.

The legacy of Burke & Gilman

Judge Thomas Burke lived in Seattle until his death in 1925 and his biographer Robert C. Nesbit chose the title “He Built Seattle” for his book, to express Burke’s involvement in every aspect of the growth of the city.

Judge Thomas Burke lived in Seattle until his death in 1925 and his biographer Robert C. Nesbit chose the title “He Built Seattle” for his book, to express Burke’s involvement in every aspect of the growth of the city.

Daniel Gilman, who lived in Seattle for a shorter time, has been honored in the name “Burke-Gilman Trail” because without his involvement in fundraising, the railroad would not have been created.

Daniel & Grace Gilman went to live in New York City for a time and came back to Seattle in 1906 to be with family and oversee some investments. The census of 1910 showed them in residence in Seattle at the home of James & Minnie Bothwell (Minnie was Grace’s sister).

On August 25, 1912, in Seattle, the Gilmans were passengers in a car with the Bothwells. Mr. Bothwell was driving, and the car collided with a streetcar at the intersection of Westlake & Mercer Streets. The Bothwells and Gilmans were shaken up and bruised. At the time, their injuries did not seem serious, but Daniel Gilman soon began to decline in health.

After a few months, with colder weather coming on, Daniel & Grace Gilman went to Pasadena, California, and stayed with Grace’s younger sister, Alice Gould. Daniel Gilman never recovered, and he died at age 68 on April 27, 1913.

Daniel Gilman’s death notice in one of the Seattle newspapers noted that “despite his large interests in developing the Northwest country, Mr. Gilman never sought public recognition and was not widely known to the public.” It was noted that at the time of Daniel Gilman’s death, his brother L.C. Gilman was assistant to the president of the Great Northern Railway Company.

Postscripts:

One of the ways to trace family histories is through the free resource called Find A Grave. The Find A Grave posting for Grace Gilman’s mother, Rosilla Philura Fogg Thorndike (1828-1917) includes a newspaper death notice listing her surviving children. This sent me on a quest to find out more about the family. I used genealogy resources and newspapers to learn more about their influential lives in Seattle.

After Daniel Gilman’s death in 1913, Grace Gilman stayed with her sister Alice, and Grace died in California in 1935.

The Writes of Way blog explores the street names of Seattle. We learn that Burke Avenue, Gilman Avenue, Bothwell Street, and Thorndyke Avenue were named for these Seattle activists. The essay about Thorndyke Avenue notes that the parents, Eben & Rosilla, spelled their name Thorndike but most of the children spelled it Thorndyke, as shown on records such as marriage certificates.

Sources:

Census, City Directory, Find A Grave, and genealogical records. Washington Digital Archives has dates of birth, death and marriages.

HistoryLink Essay #1667, “Law and Lawyers in Seattle’s History,” by James R. Warren, 1999.

Writes of Way: Seattle street names. See: entries for Bothwell, Burke, Gilman, and Thorndyke.

YouTube videos:

Two members of the original Trail Committee tell the story.

The Empire Builder: James J. Hill and the Great Northern Railway; a four-part series on how the Great Northern boosted the economy of Washington State.

Books:

Stone arch which is a remnant of the Burke Building, torn down to build the present Federal Building at Second & Marion Streets in downtown Seattle. Photo by Valarie.

He Built Seattle: A Biography of Judge Thomas Burke, Robert C. Nesbit, 1961.

Seattle 1900-1920: From Boomtown, Urban Turbulence, to Restoration, Seattle in the 20th Century, Volume 1 by Richard C. Berner, 1991.

Newspaper articles:

“Gilman Death in Alaska (Captain Albert Mason Gilman),” Seattle Daily Times, August 13, 1896, page 2.

“Why Seattle is a Young Man’s Town,” Seattle Daily Times, August 26, 1906, page 35. Describes the career of Grace Gilman’s brother: “George Fred Thorndyke was born in Maine in 1865 and came to Seattle in 1883 because his father, Captain E.A. Thorndike, having made several voyages to Puget Sound in sailing ships, was convinced that this was going to be a great city, and had bought property here. He wrote back to Maine what he thought of it, and it was from these letters that his son was inspired to go West and grow up with the country.”

“D.H. Gilman is Dead as a Result of Auto Accident,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 28, 1913, page 1.

“Injuries in Accident Fatal to D.H. Gilman,” Seattle Daily Times, April 28, 1913, page 6.

“James Bothwell, Pioneer, Dies,” Seatle Post Intelligencer, May 5, 1945, page 30.

Pavillion gravesite of Thomas & Caroline Burke at Evergreen Washelli Cemetery in Seattle. Photo by Valarie.

As someone who lives on Burke Ave., very interesting. Thanks!

This article was inspired by hearing people say that they thought Burke Avenue was named for Suzie Burke, a landowner in the Fremont neighborhood! No relation to Judge Thomas Burke, though. You can see that I have written a parallel article on the Fremont History webpage as I am also doing that, now! https://www.fremonthistory.org/wp/the-burke-gilman-trail-in-fremont/