Charles H. Baker is a little-known early Seattleite though his legacy affects every person living in Seattle today. Baker conceived of and built the electrical generating plant at Snoqualmie Falls which began producing electricity on July 31, 1899, and which continues to operate today.

Charles Baker never lived in Wedgwood but he owned land and filed two plats in 1889 and 1890, along with a group of land speculators and investors. It is ironic that although Baker was one of the earliest land owners in Wedgwood, Wedgwood was one of the last neighborhoods of Seattle to get electricity (about 1923.)

Wedgwood might have been developed earlier if it had not been for the unfavorable economic conditions of the 1890s in Seattle.

In the 1880s some parts of Wedgwood were the homestead claims of Civil War veterans who came out West from other states. One Civil War veteran, Capt. DeWitt C. Kenyon of Michigan, spent about fourteen years in Seattle before retiring to California. Capt. Kenyon had 160 acres of land, made up of four forty-acre squares. One of the forty-acre squares was south of NE 75th Street and included the present site of Eckstein Middle School. The other three-fourths of Capt. Kenyon’s land was from NE 75th to 80th Streets, 30th to 45th Avenues NE.

When Capt. Kenyon moved to California he left his property to be sold by an agent appointed attorney-in-fact. On February 29, 1888, the entire 160 acres was sold for $2550 to Charles H. Baker and a consortium of real estate investors. A photo of the title abstract is at the end of this article.

A young man sets out to make his fortune

Charles H. Baker was only 23 years old and not yet married when he arrived in Seattle in 1887. He had a civil engineering degree from Cornell University in New York and he obtained work in Seattle as a surveyor for the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railroad. (The SLS&E was organized by Judge Thomas Burke and Daniel Gilman, and today’s Burke-Gilman Trail follows the old railroad line.)

Snoqualmie Falls, located almost forty miles east of Seattle in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains, was already known to early Seattleites as a scenic site. The SLS&E organizers wanted Baker to lay out an extension of the railroad route to pass close by the Falls which they envisioned as a picnic destination. Baker, however, had other ideas. When he saw the Falls he immediately thought of the potential for generating hydroelectric power. He called Snoqualmie “the wasting waterfall” because its power was as yet unharnessed. He began to make plans to put the waterfall to work to bring electricity to the cities of Seattle and Tacoma.

Streetcars come to Seattle

Representatives of Thomas Edison, inventor of electric lights in 1882, came to Seattle on March 22, 1886, about a year before Baker arrived. After giving a convincing exhibition of how electric lights worked, representatives and local businessmen formed the Seattle Electric Company. They obtained a franchise from the Seattle City Council for electric streetlights. On March 31, 1889, the first electric streetcars began running in Seattle. After Seattle’s Great Fire of June 6, 1889, the streetcars still ran, which greatly increased public confidence in the new technology of electricity. At that time, electricity was used only in downtown Seattle for lights and the new streetcar system; electricity was not yet used in private homes.

Edward C. Kilbourne was vitally involved in early development in Seattle, including streetcar lines. Photo from Bagley’s History of Seattle, 1916.

After 1889 many different investors wanted to build streetcar lines in Seattle so that the lines would go out to areas which they wanted to develop. After the Great Fire, Edward C. Kilbourne received the City of Seattle’s franchise to restore the damaged electric power grid. Since Kilbourne was one of the developers of the Fremont neighborhood, after the Fire he began extending an electric streetcar line out Westlake Avenue along the western edge of Lake Union and north into Fremont.

From Fremont, streetcar lines were eventually built going west to Ballard and east to Wallingford. These suburbs had begun increasing in population even before the Great Fire of June 1889. There had been other fires before that one, and people understandably wanted to move farther away from the frequent-fire-zone of the downtown Seattle core. This is how Fremont originally became The Center of the Universe: you had to travel by streetcar through Fremont to get to anywhere in north Seattle. Later the Interurban rail line also went through Fremont on its way to Everett. This history is commemorated by the Waiting for the Interurban statue at N. 34th Street and Fremont Ave N., at the first intersection just north of the Fremont Bridge.

Edward Corliss Kilbourne was the nephew of Corliss P. Stone, one of Seattle’s earliest mayors, and Kilbourne had named one of Fremont’s streets for his hometown of Aurora, Illinois. From Fremont, Kilbourne kept on moving in a northeasterly direction to develop more streetcar lines to more of his investment properties in north Seattle.

In 1883 a group, the Lake Washington Improvement Co., had been formed to promote the building of a ship canal to connect Lake Union out to Puget Sound. Corliss P. Stone was a member of that group and 1883 was the year that his nephew came to Seattle.

Fremont’s early developers coordinated with developers of Green Lake and Woodland Park to extend streetcar lines. A streetcar to Guy Phinney’s private zoo, shown here in 1891. Photo courtesy of Seattle Municipal Archives Item 30713.

Investors like Kilbourne and others kept advancing out to the north/northeast of downtown Seattle because they believed a canal and bridges would soon be built, which would enhance the property values in north Seattle.

Guy Phinney, who had a private zoo, persuaded Kilbourne to extend the streetcar line to bring tourists to his estate, which became today’s Woodland Park Zoo. Next Kilbourne entered into a partnership with William D. Wood, developer of Green Lake (and also a member of Lake Washington Improvement Co.) By the 1890s Green Lake was a popular residential neighborhood with an electric trolley line encircling the lake, and Kilbourne built his own house there.

Baker buys land in northeast Seattle

In 1888 Charles H. Baker married and brought his new wife, Gladys, to live in Seattle. In January 1889 the couple filed a plat for some of the land Baker had previously bought (former Kenyon homestead claim) in what is now Wedgwood. The land on the east side of 35th Ave NE, from 35th to 45th Avenues NE, NE 75th to 80th Streets, was given the name Oneida Gardens. A year later, in January 1890 the couple named the land to the west, from 30th to 35th Avenues NE, the State Park plat.

To file a plat means to have land surveyed to show where streets should go and divide up the land into residential lots. Filing a plat usually means that the owner intends to offer lots for sale. When landowners file a plat, they give it a name, but they do not have to give the reason for the name they choose. We know that Gladys Baker was from Oneida, NY, so I believe that is the likely origin of the plat name Oneida Gardens. We know that Charles Baker attended Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. In 1885, during the time that Baker was at college, Niagara Falls was made the first state park in the USA. My guess is that the State Park plat name which the Bakers chose was a reference to that event.

An Argus magazine cartoon version of William D. Wood, circa 1900, shows him riding his streetcars out to his residential development properties.

Another possible reason for the State Park plat name might have been to attract buyers to the Baker’s plat as a scenic, park-like area. Just as the SLS&E railroad organizers thought of bringing picnickers to Snoqualmie Falls, some of Seattle’s earliest streetcar lines had parks or public picnic grounds at the end of the lines near residential developments.

One of the Baker’s co-investors, William D. Wood, was one of the biggest land developers in north Seattle and was responsible for the creation of Green Lake as a residential neighborhood. Wood was also a heavy investor in streetcar lines because he knew that transportation would make it possible for people to live in an attractive, tranquil area such as Green Lake and commute by streetcar to places of employment.

William D. Wood, along with his father-in-law John Wallingford, were the namers of the Maple Leaf neighborhood in north Seattle because of their plat name, Maple Leaf Addition to Green Lake Tract. That enormous tract stretches from 5th Ave NE to 25th Ave NE, so it includes some of present-day Wedgwood from NE 85th to 95th Streets on Wedgwood’s western border. Charles Baker was one of the co-investors in that plat, filed in March 1888 before he was married, when Baker was newly arrived in Seattle. This shows that Baker became involved with other land investors early on and probably he hoped to learn from Wood and others about where to buy land for future development. Baker may have thought that his Oneida Gardens and State Park plats would become the next “streetcar suburbs” like the ones that William Wood was developing. At the end of this article is a photo of the original Title Abstract of 1888, showing Baker’s land purchase along with the other investors.

It is likely that Baker thought that lot sales from his land investments in Oneida Gardens and State Park would generate income to finance his dream of building a hydroelectric plant. Baker seemed to make all of his plans around his goal, and he didn’t intend to work for other people while working toward his dreams. He left the employ of the SLS&E railroad and started his own construction company. He was hired by Seattle pioneer David Denny to build an electric streetcar line to the University District.

Perhaps Baker thought that the University District streetcar line would eventually extend to his Oneida Gardens and State Park plats and he would be able to sell lots at a profit as William Wood was doing at Green Lake. But the economic crash called the Panic of 1893 caused Charles Baker’s plans to collapse, because the streetcar project went bankrupt. David Denny was unable to pay him and Baker was left owing money to subcontractors.

The Wedgewood Estates apartments on NE 75th Street was originally called Oneida Gardens when the complex was built in 1949. Oneida Gardens was the plat name and it fell into disuse after the name Wedgwood characterized the neighborhood.

The (future) Wedgwood area: too remote

As it turned out, Baker’s land investment in (the future) Wedgwood neighborhood was unprofitable, because the land was remote and unreachable. Wedgwood was a failure as a streetcar suburb, because the streetcars never got there. If Charles Baker’s plans had succeeded, perhaps the neighborhood would now be called Oneida. Instead, the neighborhood did not acquire an identity and a definite name until the Wedgwood housing developments were built by Albert Balch in the World-War-Two period of the 1940s and 1950s.

Seattle had been growing in the late 1880s and the Great Fire of June 6, 1889 only increased the development boom. There was unbounded enthusiasm that Seattle would be reborn out of the Fire and would rise to greatness. To get a sense of the optimism of real estate developers of that era, we can look at statistics on the number of plats that were filed. Plats indicate that the owner expects to sell lots for people to build houses and live in the subdivision, such as Baker’s Oneida Gardens and State Park plats filed in 1889-1890.

On two other plats in Wedgwood, Pontiac and Manhattan Heights filed by Joseph Doheny in 1890, Charles Baker was listed as the engineer who did the surveying to lay out the lot plans. It had taken 34 years (1853 to 1887) for developers to create 168 subdivisions in all of King County, with most filed in the vicinity of Seattle. In just three years from 1889 to 1891, more than 400 new subdivisions were filed. (Statistics from page 12, Early Neighborhood Historic Resources Survey Report, see source list.)

Baker’s investment: from boom to bust

There are a number of plats in Wedgwood which were filed during these boom years of 1889 to 1891, such as Mary J. Chandler’s, which, like Baker’s, was ultimately unsuccessful because few lots were sold.

King County Tax Assessors records show that most of the Baker’s Oneida Gardens plat was bought out by a banker, Robert R. Spencer (depicted at right in one of the Argus magazine cartoons of 1906, see source list.)

One of the earliest purchasers of lots in Baker’s State Park Addition was Frank Vickers Cook. Cook bought lots in (the future) Wedgwood on December 15, 1891 and held the property until 1946.

As of 1901 Charles Baker still owned some lots in the State Park plat but King County foreclosed for delinquent property taxes and sold the lots at auction. The same was true of Joseph Doheny’s Pontiac and Manhattan Heights plats; they were sold for back taxes. Tax assessors records for this time period around 1900 show that almost no one lived in what would later become the Wedgwood neighborhood. It was too remote and no roads had yet been built to access this inland area, on a ridge which later became 35th Ave NE.

In 1893, after the financial collapse of the streetcar project, Charles Baker took a job at Merchants National Bank in Seattle. According to his own account, during the next five years at his desk at the bank Baker spent much of his time working on designs for a power plant at Snoqualmie Falls. Charles had come from a wealthy family but wanted to come out to Seattle and prove himself by making his own way. He had not succeeded, but because he did have a good relationship with his father, Charles decided to go home and ask for money to build the Snoqualmie Falls power plant.

Baker’s trip to consult his father

Power station with three Tesla AC generators at Niagara Falls, November 16, 1896. Courtesy of TeslaSociety.com

Charles’ father, William Taylor Baker, was a businessman in Chicago and was active in community affairs. He had been president of a world’s fair in Chicago called the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. At that world’s fair George Westinghouse had introduced alternating electrical current, which was better than Edison’s direct current because it could be transmitted over long distances. Using this technology the Niagara Falls power plant soon lit up Buffalo, NY, which was 26 miles away from Niagara, attracting large numbers of new businesses which needed power sources.

In Charles Baker’s meeting with his father, William Taylor Baker readily agreed to finance his son’s efforts to build a power plant at Snoqualmie Falls to supply Seattle and Tacoma. With his father’s good name and good credit standing on the project, Charles Baker would be able to order equipment and hire workers.

Baker starts work at Snoqualmie Falls

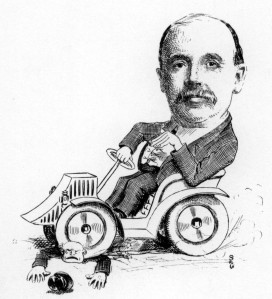

Charles Baker shown in an Argus magazine cartoon, sitting on Snoqualmie Falls and holding the electric lines of a streetcar.

By 1898 Charles Baker had bought up all the land around Snoqualmie Falls and he began working on the world’s first power plant to be constructed underground, bored through solid rock next to and underneath the Falls. In sixteen months, the plant was completed and on July 31, 1899, a powerhouse at Third & South Main Streets in Seattle received the electricity which had been generated 38 miles away.

But while Baker had been working so hard on the power plant, a Boston-based national cartel, Stone & Webster, was organizing to take control of the Seattle Electric Company. In those days there was not any municipal ownership of utilities in Seattle, and private companies fought for dominance.

By the time Baker applied to the City of Seattle for a license to operate an electric company in 1899, he had been locked out of the market. Stone & Webster had bought the favor of Seattle City Council to make franchise restrictions.

Things continued to get worse for Charles Baker. City directory listings of different residences for each of them, show that Charles and his wife Gladys had separated due to the strain of Baker’s obsession with the power plant. Then on October 6, 1903, Charles’ father died unexpectedly at his home in Chicago. William Taylor Baker left no will and there was no written agreement as to ownership of the operations at Snoqualmie Falls. The estate administrator wouldn’t recognize Charles’ claim to a “handshake” agreement with his father that they would share ownership equally. On paper, WT Baker’s estate was technically the 100% owner of the generating plant at Snoqualmie Falls. Ever-watchful of an opportunity, Stone & Webster went to Chicago and offered cash to buy out the ownership, and by 1904 Charles Baker was forced out of his own power plant.

Baker leaves Seattle

In 1904 Charles Baker left Seattle, moved to Florida and had a successful career there as an engineer for railroads. His wife Gladys and their three children continued to live in Seattle and they were active in the community. Mrs. Baker was one of the founding members of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church and of the Arboretum Foundation. She died in Seattle at age 82 in 1948.

The municipal ownership struggle

Struggles over municipal ownership of resources such as water, electricity, parks, ports and transit began with the Populist Movement in Washington State in the 1890s. There were decades of struggle with privately-owned suppliers of water and electricity. To make water and electricity available to the public at reasonable rates, in 1902 the City of Seattle built a hydroelectric plant on the Cedar River, which was the USA’s first municipally owned hydroelectric project (info source: history records of Seattle City Light.)

Port District legislation was passed by the Washington State Legislature in 1911; prior to that time the Seattle waterfront was controlled by railroads. It was not until 1934 that the Stone & Webster electric utilities monopoly was finally broken by New Deal anti-trust legislation under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Finally in 1951 City Light was able to buy out the rest of the private electric ownership in and around Seattle. Seattle is known today as having one of the lowest-cost electric rates in the USA, thanks to the foresight of City fathers and decades of struggle to gain municipal ownership of resources.

Sources:

THANK YOU to Seattle historian and property research expert Greg Lange for all his help with research and references.

Capitol Hill streetcars: for a study in contrasts of how different neighborhoods of Seattle developed, read this history of the apartments and commercial growth around streetcar lines of Seattle’s Capitol Hill. In contrast to Capitol Hill and other close-in neighborhoods, Wedgwood had no streetcars or apartments. In the early 1900s Wedgwood had few stores, and it became an automobile neighborhood early on, due to lack of population density and the distance needed to travel to places of employment.

Early Neighborhood Historic Resources Survey Report and Context Statement by Greg Lange and Thomas Veith, 2005 (revised 2009.) The report is listed as “Residential structures constructed prior to 1906” under context statements, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods historic preservation page.

HistoryLink essay topics: City Light; Edward Corliss Kilbourne; Electric trolley lines; Green Lake; Maple Leaf; Municipal Ownership Movement; Snoqualmie Falls; William D. Wood.

Men Behind the Seattle Spirit – The Argus Cartoons. H. A. Chadwick, editor, 1906. Seattle Room, Seattle Public Library/Central, R.B.0 Ar38M. Cartoon depictions of Charles H. Baker, Robert R. Spencer and William D. Wood.

The Power of Snoqualmie Falls (2008): Available as a DVD from the Seattle Public Library, or online at this link.

Title Abstract: record of sale of land from DeWitt C. Kenyon to the investors group of Charles H. Baker, C.C. Calkins, W.J. Jennings, M. Stixrud, Wm D. Wood. Richard Osborn, attorney-in-fact, February 29, 1888. Original document at the Puget Sound Regional Archives, Bellevue, WA.

Title abstract showing the purchase of property owned by Capt. DeWitt C. Kenyon, a purchase of 1888 by Charles H. Baker and some co-investors. Document on file at the Puget Sound Regional Archives, Bellevue, WA.

I must admit that I had previously thought that “Center of The Universe” was a joke. Thank you for educating me.