Early surveyors had to try to draw straight lines through rough terrain. This surveyor on a stump is probably at Fort Lawton, June 27, 1900. Photo courtesy of UW Digital Collections KHL272.

Wedgwood Rock probably first came to the attention of white settlers in the 1870s. A land survey of north Seattle was done in 1855, but there was no notation of the existence of the Rock.

The surveyors of 1855 described the terrain in their notes but the surveyors were not explorers; using a compass and chain, they walked straight across grid lines to mark what would eventually become arterial streets. Walking east and west across what is now NE 75th Street, the survey party did not see the Rock. It was only about 1,000 feet south of where the surveyors walked, but the Rock was hidden in a dense forest of trees. At that time (1855) no white settlers had yet come to live in northeast Seattle.

Copyright notice: text and photos in this article are protected under a Creative Commons Copyright. Do not copy without permission.

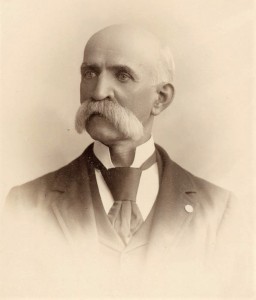

William Strickler, who led the six-man north Seattle survey party of August and September 1855, had chosen land for himself in what is now the business district of the Fremont neighborhood. Just to the west of Fremont, in 1853 John Ross had made a homestead claim on land which today is on both sides of the ship canal, at the present site of Seattle Pacific University and southwestern Fremont. Ross Playground at 4320 4th Ave NW marks the northern borderline of Ross’s two sections of land claims.

The Puget Sound Indian War which began in October 1855 caused widespread fear among the white settlers of the Seattle area, and it was another ten to twenty years before homesteaders again ventured to stake claims in remote north Seattle. John Ross’s cabin was burned down during the Indian War and Ross didn’t return and rebuild until the 1870s. In 1868 William Goldmyer filed a claim for land at Sand Point, one of the earliest claims in northeast Seattle. Goldmyer was not in Seattle during the Indian War and perhaps for that reason he was less susceptible to fear. Goldmyer was only 25 years old when he arrived in Seattle and he was young and enthusiastic about having his own land.

Wedgwood Rock, located at 7200 28th Ave NE in Seattle, was called Lone Rock in 1881 when a group of early Seattle settlers gathered for a Fourth-of-July picnic.

In the 1870s Civil War veterans from other states came to take up the offer of free land out West as credit for time served in the Union Army. In 1873 two brothers, Robert and William Weedin, came from Missouri to acquire land in Seattle, Washington Territory (Washington had not yet become a state.) Under provisions of homestead laws these men received land free, because they were Civil War veterans.

Each Weedin brother improved their claim by building a house and clearing the land. An article in The Seattle Times, February 6, 2010, told of one of Robert’s sons, John F. Weedin, who became a policeman in Seattle and was killed in the line of duty in 1916, at age 44. A street, Weedin Place near Green Lake, marks part of the site of the original Robert Weedin land claim.

This photo of Wedgwood Rock may be as early as 1890. It was then called Lone Rock or Big Rock. Photo in the William F. Boyd Album, University of Washington Special Collections.

William Weedin, Robert’s younger brother, homesteaded 160 acres in what is now “southern” Wedgwood, including the site of Wedgwood Rock at the intersection of NE 72nd Street & 28th Ave NE.

The following letter to the editor of a Seattle newspaper, the Daily Intelligencer, tells of a Fourth of July celebration in 1881 at what was then called Lone Rock. Our thanks to Greg Lange, Seattle history and property research expert, for finding and contributing this historical news item.

The Fourth at Interlake

Editor Intelligencer:

I suppose Interlake is unknown to many of the readers of your valuable paper. It is not a city or even a village, but it is the name of our school district (No. 25 of King County) situated between Lakes Union, Washington and Green; hence the name.

The place selected to celebrate our glorious old Fourth is a romantic one, and I doubt if another such could be found in the Territory. On the farm of Mr. William Weedin in a dense forest is a single rock 80 feet in circumference and 19 feet in height, rather oval-shaped, covered with a solid network of moss and interspersed with liquorice, with its graceful fern-shaped foliage hanging in festoons around it. From the top of this rock our young friend Martin Weedin, scarcely 16 years of age, read the Declaration of Independence in a very creditable manner, after which we had a few patriotic songs.

Next in order was dinner. It was the best our farms afforded, from a spring chicken down to the delicious dish of raspberries and cream. Some of Seattle’s fairest ones came with baskets filled with delicacies and joined with us in celebrating our national holiday. After the appetite was well cared-for, the fun commenced in games, and three large swings were constantly in use by the little ones, some of whom, however, were old enough to vote.

By this time the sun, in the far distant west, gave us warning of the coming night. Before closing the day’s festivities more music was called for and all joined in a variety of Sabbath school songs, with instrumental accompaniment. A large ladder was then placed so all who wished could get on top of the lone rock and view the surroundings from this lofty stand, while the Star Spangled Banner, by a quintette of singers, closed one of the pleasantest of Fourths of July. Forty-two persons were present. Everything went off harmoniously and in a manner long to be remembered with satisfaction by all who celebrated at the lone rock. (Source: Letter to the Editor – author’s initials C.F.D., Daily Intelligencer newspaper, Seattle, July 6, 1881, page 4.)

The author of the above letter gave few names. William Weedin is mentioned because the Lone Rock, as it was then called, was part of his homestead claim land. His brother Robert’s eldest son, Martin, read the Declaration of Independence at the Fourth of July celebration. The picnickers were patriotic, as we know that both of the Weedin brothers were Civil War veterans.

Viola Kenyon in 1910 (age 70.) Photo by Asahel Curtis, courtesy of the Seattle Public Library Historical Photograph Collection.

The federal census of 1880, taken a year before this picnic at the Rock, listed the names of those who lived in northeast Seattle’s Lake Washington District, as it was called. Judging from the names of the Weedin’s nearest neighbors as seen on the census of 1880, there were probably several other Civil War veterans among the group of forty-two adults and children who gathered at the 1881 Fourth of July celebration, including the Dunham and Kenyon families.

The initials of the writer of the letter to the editor, C.F.D., match those of Charles F. Deibert, another one of the Civil War veteran/homesteaders of the Wedgwood area. However, it is possible that C.F. Deibert was the one who carried the letter to the newspaper office in Seattle but was not the author. I suspect that the author of the above letter was one of the women in the group, probably Charles Deibert’s sister-in-law Viola Kenyon who was the teacher at the school for the homesteaders’ children.

Charles Deibert had been married to Addie Dunham, younger sister of Viola Kenyon. Addie died in October 1880 at age 29, leaving Charles F. Deibert widowed for the second time. Of the group of homesteaders at the picnic of 1881, Charles F. Deibert stayed in Seattle the longest. He finally moved to an “old soldiers home” in California in 1901. Viola Kenyon returned to Washington State after her husband Capt. DeWitt C. Kenyon died in California.

The William Weedin residence, Coupeville, Whidbey Island, circa 1900. Photo courtesy of UW Digital Collections #WAS1230.

Despite the delights of the Lone Rock, the William Weedin family did not stay long in north Seattle. In 1888 they moved to Useless Bay, Whidbey Island, not far from Coupeville where another glacial boulder is located.

When the William Weedin family moved to Whidbey, their north Seattle property was left in the hands of a real estate agent to be sold. The Lone Rock was next acquired by the Miller family, early residents of Washington Territory.

The final phase in the saga of the Rock was its acquisition as a housing development beginning in the 1940s. Wedgwood Rock remains today, surrounded by houses.

This property card from the tax assessors office is meant to show the house at 7200 28th Ave NE, but of course we are more impressed with the view of the Rock in 1948. Photo courtesy of the Puget Sound Regional Archives, repository of the property records of King County.

Sources:

“Sand Point on Lake Washington is first surveyed on August 29, 1855, and opened for settlement.” HistoryLink Essay #2215, Greg Lange, January 15, 1999.

“Seattle Neighborhoods: Sand Point’s first settler is William Goldmyer on September 5, 1868.” HistoryLink Essay #2219, Greg Lange, January 1, 1999.

Land Patent of William Weedin #WAOAA 071911, Bureau of Land Management. http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/

“Luther Weedin.” Son of William Weedin, the article tells about the Weedin family’s arrival in Seattle and how they lived. Seattle and Environs 1852-1924, Cornelius Hanford, 1924. Vol. 2, p. 448-51, University of Washington Suzzallo Library, Special Collections.

“The Fourth at Interlake,” Daily Intelligencer newspaper, Seattle, July 6, 1881, page 4.

Consultation: Nancy Robison, Kenyon/Dunham family researcher, via e-mail July 2013.

William Strickler and David Phillips co-led a team which walked out a grid in north Seattle in 1855. The six–mile square is called Township 25. The top line is 85th Street. Township 26 is the next one to the north, extending from 85th to 205th (the county line). Wedgwood Rock is marked with pencil x’s next to the numeral 4, which shows the L-shaped homestead claim of William Weedin, consisting of four, forty-acres squares = 160 acres.