On the evening of July 4, 2025, a speeding car plowed into the Mioposto restaurant at 3426 NE 55th Street. Diners were showered with broken glass, but fortunately no one was killed. Immediately work began to reinforce the building’s storefront, as the main supporting post had been sheared away.

On the evening of July 4, 2025, a speeding car plowed into the Mioposto restaurant at 3426 NE 55th Street. Diners were showered with broken glass, but fortunately no one was killed. Immediately work began to reinforce the building’s storefront, as the main supporting post had been sheared away.

Above the storefronts, the parapet of the building has a letter H outlined in brick & tile, which set me on a quest to know what the “H” stood for. I think it is likely the initial of John Stauffer Hudson who constructed the building in 1925.

This blog article will trace the background of John Hudson, his career as a builder in Seattle, and the story of the building at 3426 NE 55th Street.

Civil War veterans in Seattle

One of the threads of Seattle history is the influence of Civil War veterans who came from many different states of the USA, to start new lives in this new city. Some veterans started arriving very early, in the 1870s, only five years after the end of the Civil War. Veterans like Daniel Gilman, George Boman and H.C. Henry were influential in railroad development and other investment projects in Seattle.

Veterans were still coming to Seattle after the year 1900 even though they were by then age sixty or more. One of these was Henry Hofeditz who left Illinois and arrived in Seattle in about 1902, bringing his entire family of five adult children with him. Henry became an active member of the Green Lake chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic veterans group.

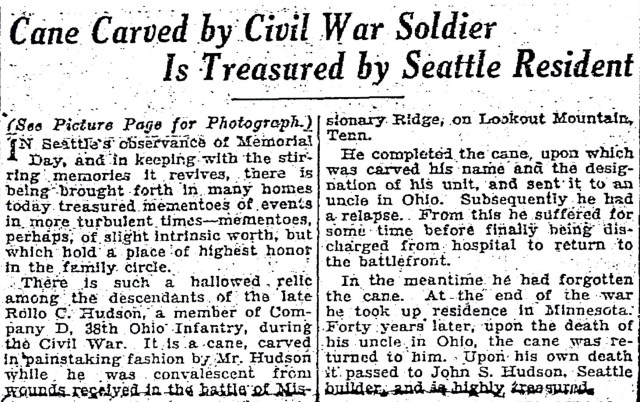

Rolla C. Hudson was another Civil War veteran who was sixty years old when he arrived in Seattle in about 1902. He and all eight of his adult children settled in the Green Lake area. We can only guess at the reasons for this radical move from Minnesota to Seattle; perhaps all the Hudson family members were ready to find new economic opportunities in Seattle, and they wanted to stay together.

Rolla Hudson’s journey

Rolla Hudson was born in Ohio in 1843 and by the time he was six years old, both of his parents had died. Rolla and his two younger sisters were each farmed out to live with different families in their village.

At the time of the Civil War in 1861-1865, Rolla served with an Ohio unit of the Union army.

After the Civil War, by or before 1870 Rolla and his sisters had all moved to Minnesota, where they married and started their own families. Both of Rolla’s sisters married Civil War veterans.

Despite, or possibly because of, having been orphaned, Rolla and his sisters never lost their sense of family connection. The siblings stayed close throughout their lives. Rolla gave one of his sons the name of a brother-in-law, John Stauffer, and used other family names for his children.

Rolla Hudson & his wife Martha were about sixty years old when they moved to Seattle and it is amazing to see the family closeness which caused their adult children to join the journey. After Rolla’s death in 1923, on Memorial Day every year in May, the family remembered their father and honored his Civil War service.

The Hudson siblings also carried on the knowledge of their early-American family heritage. They knew that they were descended on both their mother and father’s sides, from ancestors who had fought in the American Revolution.

John Stauffer Hudson in Seattle

Rolla’s son John Stauffer Hudson was about twenty-four years old when he came to Seattle and like his father, he worked as a carpenter. John and his brother Harry gradually became contractors and investors in new buildings, and they did architectural design work, as well. Typically, John S. Hudson would buy property, construct a building and then sell it to other investors. In the 1920s he became one of the foremost builders of apartments on First Hill and Capitol Hill in Seattle.

A new type of dwelling: apartments

Over its first fifty years, 1851-1901, Seattle had hotels, lodging houses and boarding houses. A hotel implies that guests are from out of town and just need a short-term place to stay. A lodging house has the same design as a hotel in that there are services such as cleaning of rooms, but it is understood that the residents are living there seasonally or long-term. They take meals elsewhere such as at their company’s employee cafeteria or out at a restaurant. There were many lodging houses in Seattle as the early economy was geared to men doing labor such as in sawmills.

A boarding house is typically a private home where the owner is renting out rooms, and very often some meals are provided by the homeowner. Taking in boarders was one of the most common ways for a widow to support herself.

An apartment is defined as a self-contained living unit having its own kitchen and bathroom, in a building of multiple units having a common entrance from the street.

The first apartment building in Seattle, the St. Paul, opened in 1901, built by an investor from St. Paul, Minnesota. The St. Paul apartment building still stands today at 1206 Summit Avenue & 1302-1308 Seneca Street, with three addresses because of its entrances on different sides.

The first apartment building in Seattle, the St. Paul, opened in 1901, built by an investor from St. Paul, Minnesota. The St. Paul apartment building still stands today at 1206 Summit Avenue & 1302-1308 Seneca Street, with three addresses because of its entrances on different sides.

The St. Paul was meant to appeal to well-to-do people because of its First Hill location and very large apartments. Apartments at St. Paul averaged 1400 square feet and most had three bedrooms. Each apartment had its own bathroom, kitchen, dining room, and parlor.

Very soon after the St. Paul opened, the classified listings in the Seattle City Directory added a heading for apartment buildings, separate from the listings of hotels and lodging houses.

The increase in the numbers of apartment buildings in Seattle was based on the growing population, growing economic prosperity and improvements in infrastructure such as electricity and water supply systems. Things which we consider normal today, such as hot and cold running water and electrical outlets, were innovations.

Electric refrigeration had not yet come into use in the early 1900s, so these early apartments each had a back porch where ice would be delivered for the household ice box for keeping food. By the 1920s, electric stoves and refrigerators were being installed in Seattle apartments along with other amenities such as phones and radios. The availability of elevators caused apartment buildings to be built taller and taller.

Up through the 1920s the population of Seattle continued to grow, along with streetcar routes which could take a person from the hills surrounding downtown, to work and back again. Apartment buildings met the needs of workers to live more comfortably, and families with children began living in apartments, too.

Seattle’s booming economy in the 1920s

As a builder, John Hudson rode the upward wave of the good economic conditions in Seattle in the 1920s. One of the trends of that decade was the construction of apartment buildings which were replacing old single-family homes on First Hill and Capitol Hill.

The area around the present site of Virginia Mason Hospital near Boren & Spring Streets, is dense with apartment buildings constructed by John Hudson. One of his buildings, the Hudson Arms Apartments at 1111 Boren Avenue (built 1924) was purchased by the hospital and demolished after a 1997 fire damaged the building.

The Northcliffe at 1119 Boren Avenue, built by Hudson, was demolished in 2008 for expansion of the hospital. Another Hudson building, the Rhododendron, is now called the Inn at Virginia Mason at 1006 Spring Street. The Rhododendron Building shows Hudson’s signature mark, the letter H, on the parapet.

The Rhododendron Building at 1006 Spring Street has John Hudson’s signature mark, the letter H, on the parapet. The building is now known as the Inn at Virginia Mason. It has a Rhododendron Cafe with original windows depicting the flowers. Photo courtesy of JRV.

No one “commissioned” Hudson for these buildings. Typically, he would build an apartment building and then sell it to an investor. He seemed to have no trouble finding buyers. Like the trend of investment in the stock market, in the 1920s people were getting into real estate investment in apartment building ownership which would pay them an income.

Some of the First Hill apartment buildings for which John Hudson was the contractor, were designed by his brother Harry Hudson. The brothers harkened to their early American heritage by giving buildings names such as the John Alden, built in 1924 at 1019 Terry Ave.

Some of the First Hill apartment buildings for which John Hudson was the contractor, were designed by his brother Harry Hudson. The brothers harkened to their early American heritage by giving buildings names such as the John Alden, built in 1924 at 1019 Terry Ave.

John Alden was the name of a leader of the Pilgrims who arrived in 1620 on the Mayflower and was one of the founders of the Plymouth Colony. The John Alden apartment building has an oak front door and leaded glass sidelights depicting the Mayflower.

Another early-American reference was Faneuil Hall (pronounced fan-yule) at 1562 East Olive Way, built by the Hudson brothers in 1928. Its name was a tribute to Faneuil Hall in Boston which was built in 1742, famous as a place of speech-giving for American independence.

The Hudson brothers gave the names Lowell-Emerson to the apartment buildings completed in 1928 at 1102-1110 8th Avenue. Its names honored American writers of the 1800s.

John Hudson gave old English place names to some of his apartment projects, such as the Northcliffe at 1119 Boren Avenue (demolished 2008 for expansion of the Virginia Mason hospital campus) and the Chasselton, built in 1925 at 1017 Boren Avenue.

These two buildings, the Northcliffe and the Chasselton, were designed by well-known Seattle architect Daniel R. Huntington. His name added prestige and caused the new apartment buildings to easily sell to investors.

Daniel Huntington had been City Architect from 1912 to 1921, designing many fire stations and the Lake Union Power Plant. His final project for the City was the Fremont Branch Library at 731 North 35th Street.

In 1925, Huntington designed a house for his own family at 1800 East Shelby Street in Montlake, for which John Hudson was the contractor. Today it is a fraternity house.

The storefront on NE 55th Street

It hardly seems possible that John Hudson could have been involved in so many construction projects at once. In 1925, which seemed to have been his busiest year, Hudson was overseeing construction of tall apartment buildings in downtown Seattle, but in that year he also built a one-story storefront building at 3426 NE 55th Street in northeast Seattle. Perhaps Hudson had intended to hold it long-term for rental income, after branding the building with an H on the parapet. Instead, Hudson sold the little building to an investor.

In a news article about the sale of the building, John Hudson stated that “due to the city’s expansion, the establishment of small business centers is providing an attractive class of income properties.” (Seattle Daily Times, November 14, 1926.) Hudson saw that the population of northeast Seattle was increasing in the 1920s. He did this one building project but possibly he was too busy with his First Hill apartments, to do anything more in northeast Seattle.

Lines of the streetcar tracks can still be seen on the south side of NE 55th Street nearest to the corner of 35th Ave NE. Calvary Cemetery is at left. Photo courtesy of Feliks Banel.

The building at 3426 NE 55th Street, at the intersection of 35th Ave NE, was an ideal location for stores. It was at the end of a streetcar line on NE 55th Street and surrounded by a growing residential community in the University Heights plat. The new brick Bryant School building was only a few blocks away on NE 60th Street, which was attracting more families to the area.

In 1926 George K. Becraft moved into one of the spaces in the 3426 building with his grocery store. In those early days grocery stores did not have as many products as they do today, and the small neighborhood stores like Becraft’s were not “self-service.” Products did not come in consumer packaging. If you wanted to buy a pound of coffee beans, for example, the grocer would scoop them out of a burlap sack or a barrel, weigh the amount and give it to you in a paper bag.

George Becraft had come to Seattle at age fourteen when his parents moved the family out from Rockland County, New York, in 1907. We might guess that, like many other people, Henry & Sophia Becraft heard of the growth of Seattle and the planned world’s fair, the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, to be held in Seattle in 1909, which was sure to bring more growth to the city. The AYP caused real estate companies to promote land developments in northeast Seattle such as Laurelhurst.

As an adult George Becraft worked in his father’s grocery business in south Seattle until the opportunity came to open his own store in the new building at 3426 NE 55th Street. With his wife and daughter, George moved to live nearby, at 5250 35th Ave NE.

Another of the first businesses in the building was the pharmacy of Eugene J. Pence. Pence’s Drugstore was given the prime corner space at the intersection of NE 55th Street & 35th Ave NE, where a blade sign could be seen from both sides.

Eugene Pence had been born in Missouri as his parents gradually moved their family across the USA. Eugene began his pharmacy career in Bellingham, WA. Pence & his wife then moved to the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle where he worked at the Woodland Park Pharmacy, 4250 Fremont Ave. Pence was forty-six years old when the opportunity came to open his own drugstore in the Hudson building in the corner space at 3428 NE 55th Street. He & his family moved to live nearby at 5206 36th Ave NE.

In 1927 the investor/owner of the building at 3426 NE 55th Street, built an additional building just behind it, at 5507 35th Ave NE. He rented it out to be the office of a real estate agent, Mr. Barr.

In 1927 the investor/owner of the building at 3426 NE 55th Street, built an additional building just behind it, at 5507 35th Ave NE. He rented it out to be the office of a real estate agent, Mr. Barr.

In the days before cell phones, all real estate agents had an office address with a landline phone.

A very long-lasting business in the 5507 building was the Ewing & Clark Real Estate company. In recent years the building was remodeled with a second floor added and has the offices of a law firm.

One of the recent businesses in the Hudson building was Spinnaker Chocolate at 3416 NE 55th Street. They moved out in April 2025 and reopened in the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle at 3509 Stone Way.

A continuous type of business in the Hudson building over the past one hundred years, has been a barber shop in the middle space of the building at 3420 NE 55th Street. The current business, Starline Barber Shop, was undamaged by the car crash of July 4, 2025, and the business continued unaffected.

A continuous type of business in the Hudson building over the past one hundred years, has been a barber shop in the middle space of the building at 3420 NE 55th Street. The current business, Starline Barber Shop, was undamaged by the car crash of July 4, 2025, and the business continued unaffected.

The Mioposto Pizza restaurant at 3426-3428 NE 55th Street was completely destroyed by the car crash. Thankfully the building structure was repaired, and the restaurant was restored. Mioposto re-opened on December 10, 2025.

Sources:

A three-year-old great-grandson of Rolla Hudson, Civil War veteran, holds the cane which was handed down in the family. Seattle Daily Times article of May 30, 1928, page 24.

Census, City Directory listings, genealogy including Find a Grave, and newspaper searches.

Mioposto pizzeria – on their social media the restaurant gave updates on the crash which destroyed the restaurant and their plans for a new branch at Eastlake Ave.

Seattle Historic Sites Index has descriptions of some of the Hudson apartment buildings:

–Faneuil Hall at 1562 Olive Way

–John Alden Apartments at 1019 Terry Ave

–Lexington-Concord Apartments at 2402 2nd Ave

–Lowell-Emerson Apartments listed on the index as 1100 8th Ave

Shaping Seattle Architecture: A Historical Guide to the Architects, Second Edition, edited by Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, 2014. Seattle Public Library, 720.92279.

Shared Walls: Seattle Apartment Buildings, 1900-1939, by Diana E. James, 2012. Seattle Public Library, 728.31409

THANK YOU to JRV whose sharp eye noticed the letter H on the parapet of the building on NE 55th Street, which sent me on this quest to learn about John S. Hudson. She has since spotted the letter H on another building, the Rhododendron at 1006 Spring Street.

THANK YOU to JRV whose sharp eye noticed the letter H on the parapet of the building on NE 55th Street, which sent me on this quest to learn about John S. Hudson. She has since spotted the letter H on another building, the Rhododendron at 1006 Spring Street.

Postscript on the life of John S. Hudson: Hudson’s building program came to a screeching halt during the economic crash called The Great Depression in the 1930s. He suffered a great deal of financial difficulty. He was able to get a job as an appraiser with one of the “New Deal” programs started under the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The federal government hired appraisers to work with homeowners, in a loan program to pay their mortgage, so they would not lose their houses.

Full-page ad in the Seattle Daily Times, July 26, 1925, page 41. John S. Hudson advertised his work and that of subcontractors shown in the business cards.

Excellent research. Thanks for all the back story!