This blog post will tell of an African-American couple, Charles & Nora Adams, who came to live in northeast Seattle in 1912. Charles & Nora Adams were among the early residents just north of Calvary Cemetery on NE 55th Street. The Adams lived on 28th Ave NE in a plat of land, a real estate development, called Ravenna Orchard. Today the neighborhood is called Ravenna-Bryant.

A mariner on the Mississippi

In 1793 a very early act of Congress established federal support for marine hospitals. These hospitals were meant not just for military men, but for seamen of commercial vessels who might be sick or injured. In those years before the coming of railroad networks, ships were the most vital means of travel and transportation of goods to and from the ports of East Coast cities. As the USA expanded westward, the service of marine hospitals was added to the port cities of the Mississippi River and its tributary waterways.

The census of 1900 showed a long list of patients in residence at the Seamens Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, one of the major ports along the Mississippi River. The list of patients included both black men and white men. We don’t know how much actual medical help was provided to the men, but at least they had a place to stay and were given meals during their time of recuperation from any illness or injury.

Charles B. Adams, age 24 in the year 1900, was born near Memphis, Tennessee, and he’d chosen to work on river-going vessels. Work for a black man on a boat in the Mississippi River might include “fireman” as the person who stoked the steam boiler, or a cook or general laborer. The upper river line of shipping was from St. Louis, Missouri, to St. Paul, Minnesota. Perhaps Charles Adams had traveled on ships on this route, up and down the river. Perhaps it was these trips which caused him to see other perspectives of life and think of living somewhere other than the South.

St. Louis continued to be Charles’ home base for a few more years, after he married Nora, a native of St. Louis, in 1900.

By the time Charles & Nora Adams left St. Louis in the early 1900s, transportation of goods by train had become common and trains were even causing a decline in the riverboat economy. Perhaps for this reason Charles wanted to make a change of occupation away from the Mississippi River and he thought there might be more work in another port city, Seattle, Washington.

This blog article will tell the story of Charles & Nora Adams in Seattle, where they lived the rest of their lives.

Charles & Nora Adams arrive in Seattle

The Seattle City Directory first listed Charles & Nora Adams in 1908 where they became part of a new trend in Seattle, the creation of apartment buildings. The Adams were listed at a brand-new building, the Jensen, at 601 Eastlake (northwest corner of Eastlake & Mercer Streets), where Charles was the janitor. Over the next four years the Adams were listed at two other buildings where Charles was a janitor and Nora was a maid for a private family.

When apartments were first created in Seattle in the early 1900s, the buildings had rooms for a live-in janitor and sometimes there were maid’s quarters, along with a laundry area and equipment to be maintained, such as the heating plant for the building. We don’t know whether the Adams lived rent-free or whether Charles received a salary and Nora might have been paid to work as a maid or cook.

The Adams did not stay in one place very long but moved to other buildings. Their last apartment building listing was on Seattle’s Capitol Hill at the Oleta Apartments, built 1910 at 1816 Bellevue Ave, on the southeast corner of Bellevue Ave and East Denny Way. What we can surmise from the Adams’ listings in the City Directory is that they were able to find work, and they prospered so that circa 1912, they were able to buy a house.

Racial and ethnic groups in Seattle in the early 1900s

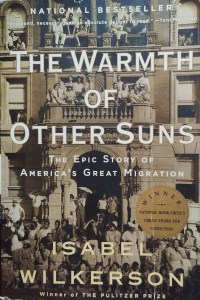

In the book The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson, the author tells the story of America’s Great Migration of African-Americans from the South to the industrial cities of the North, during 1915 to 1940. There was a tendency for African-Americans of coastal states such as Florida, to migrate to metropolitan cities of the East Coast such as New York or Philadelphia. Black people from central-south states such as Mississippi, tended to move to north-central cities such as Chicago or Detroit. These destinations reflected lines of train travel. However, there is no direct pattern of migration of African-Americans to West Coast cities such as Los Angeles and Seattle.

The census of 1910 in Seattle showed the city population at about 237,000. About 16% of the people were from Seattle or from somewhere within Washington State. About 59% came from other states of the USA. People who were born in other countries comprised 25% of the Seattle population, with Canadians the most. Japanese at 6,127 people were the fifth-largest immigrant group in Seattle behind Canadians, Swedes, Norwegians and Germans. In 1910 African-Americans in Seattle were listed at about 2,300, less than 1% of the population.

At such small numbers, it is hard to make many generalizations about black people in Seattle except that we know they were not very visible in society. We know that the Japanese had gained a foothold in the old Chinatown centered on Jackson Street, where the Japanese operated many businesses such as hotels, restaurants, laundries and shoe repair. Already in 1910 there was a pattern for black families to live east of there in what became the Central District. There were eastbound streetcar lines on Yesler & Madison Avenues, so that residential areas east of downtown grew because people could commute to work. Some of the earliest apartment buildings in Seattle were built on Capitol Hill and First Hill for this reason, that a streetcar line was nearby.

The Adams buy a house in northeast Seattle

Bryant School at 3311 NE 60th Street, built 1926. This was its second building. The first building was at the southern end of the same block and in 1918 it was named Bryant.

Very few people lived in northeast Seattle in the years before 1912 and yet a little community was developing just north of NE 55th Street, in plats that had been filed called University View and Ravenna Orchard.

Rev. John Norton and his wife Minnie Widger Norton owned land from NE 55th Street to 60th around what became the Bryant School area.

The Nortons began to sell house lots in 1906 in their plat called University View. The area was not called Bryant until 1918 when the first wood-frame school was built on NE 57th Street and was given the Bryant name. In 1926 the present brick school building was built at the north end of the same block at NE 60th Street.

At the same time as the Nortons were starting to sell lots in their University View plat circa 1906, a young attorney, Hugh Benton, became a specialist in real estate transactions and he began to sell house lots on 28th & 29th Avenues NE, just north of NE 55th Street. He recruited his brother Benjamin to move from New Hampshire and be a contractor to oversee the building of houses on these streets which were given the plat name of Ravenna Orchard.

Streetcar track lines on NE 55th Street at the corner of 35th Ave NE. Photo courtesy of Feliks Banel.

With the buildup of infrastructure for the world’s fair event to be held in Seattle in 1909, the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, community boosters like the Nortons and Bentons succeeded in getting a streetcar line extended out along NE 55th Street, all the way to the corner of 35th Ave NE. Track marks can still be seen at that corner. The wye for the streetcar to turn back on the route, was at the corner of the cemetery where the mausoleum is now.

The availability of the streetcar route as of 1909 enhanced the profitability of neighborhoods like Ravenna Orchard, adjacent to NE 55th Street, for people to be able to live there and get to work in the University District or downtown Seattle. This map is from Mike Bergman’s book, Seattle’s Streetcar Era.

Building houses in Ravenna Orchard

In the early-1900s years in northeast Seattle it was typical for people to own several lots in addition to their house lot. They might have another lot for a garden, or for keeping chickens. It later became common for people to build and sell houses on their adjacent lots, for income. This process called “infill” was the cause of 1940s houses built in-between older houses.

A German immigrant, Charles L. Petrie, lived at 5520 28th Ave NE as of 1908 and he fit the above pattern, of buying several lots and then selling them.

Widowed and aged 60 in 1910, Mr. Petrie was still working but perhaps he was thinking of income for retirement, when he sold lots adjacent to his house. We note that his occupation was “steward, seaman.” A steward on a ship could be a supervisory role in overseeing kitchen work, organizing supplies and seeing to cleaning or laundry.

We see a connection here to work that Charles Adams had formerly done on the Mississippi River shipping lanes. Perhaps Petrie & Adams met here in Seattle and this is how Charles & Nora Adams came to acquire the house next door, on the north side of Mr. Petrie’s. As of 1912, the Seattle City Directory listed the Adams living at 5526 28th Ave NE, and they owned the house.

The Adams and their neighbors on 28th Ave NE

The Driscoll house, 5536 28th Ave NE, on the north side of the Adams house. Photo of the 1937 property survey.

When the Adams moved to 5526 28th Ave NE, the house on their north side, 5536, was occupied by a young couple who were renting. Edwin C. Eichhorn, age 30, was a metalworker, a son of German immigrants and had met his wife Bessie in Ohio. The Eichhorn family was only in Seattle for a few years before returning to Ohio, and we can surmise that Bessie wanted to go back to live near her family members.

The house at 5536 28th Ave NE was next sold to Dennis Driscoll, an Irish immigrant who worked as a bridge carpenter for the Northern Pacific Railroad. His wife Eliza had been born in Nova Scotia of Irish immigrant parents.

In the book, The Warmth of Other Suns, about the migration of African-Americans from the South to the North, one of the families who were interviewed were George & Ida Mae Gladney. They left rural Mississippi in 1937 and settled in Chicago, where George eventually got a good job on the production line of Campbell’s Soup. In the 1950s the Gladneys went in together with their two grown children to pool their money and buy a house. They found a house that had been divided into three units, which could accommodate the three families. The owner, an Italian immigrant who was a car salesman, expressed that he liked them and that he was satisfied with the arrangements, as the Gladneys paid cash.

The Gladneys told how, when they moved into the house in Chicago in the 1950s, their two grandchildren were two of only four black children in the local elementary school. Four years later, all of the white families on their street had moved away and there were only four white children in the local elementary school, with all others black children. By 1980 Chicago was listed as the most segregated city in the USA as entire neighborhoods were blocked out as either black or white.

In tracing the lives of Charles & Nora Adams who began living at 5526 28th Ave NE in Seattle in 1912, I attempted to see whether other people “fled the neighborhood” due to their presence. That was not the case for the Adams’ next-door neighbors. Charles L. Petrie lived at 5520 until he died in 1932. Dennis Driscoll died suddenly in 1930 and his widow, Eliza, continued to live at 5536 until her own death in 1958. We may well speculate that the two neighboring women, Eliza Driscoll and Nora Adams, were friends.

The Driscoll’s descendants still owned their house at 5536 28th Ave NE into the 1970s. In the 1950s the Driscoll’s son bought the Adams house and in the 1970s a third generation of Driscolls, the granddaughter of Dennis & Eliza Driscoll, was living in the Adams house.

The Adams’ long occupation of their house

The Adams’ long years of occupation of their house, from 1912 to their deaths (1944 & 1962), seems to imply that either they didn’t encounter much neighborhood opposition, or they were determined to live their lives despite opposition. As mentioned above, the Adams house was bracketed by those of immigrant families who lived on either side of the Adams for many years. Perhaps they considered this African-American couple to be like themselves, outsiders/immigrants, in pursuit of the American Dream of home ownership.

Bell’s Drugstore built 1924 at 2818 NE 55th Street, shown here in a property tax assessors photo of 1937. In the 1920s the store had a book lending library.

We may wonder whether the Adams shopped for groceries on NE 55th Street or at other shopping districts, and whether they were ever refused service at local stores. Bell’s Drugstore, shown here in a photo circa 1937, opened in 1924 and for a time it had a makeshift book lending library, the ancestor of the Northeast Branch Library.

We wonder whether Charles & Nora Adams encountered any difficulty in using the streetcar line which traveled along NE 55th Street. Back in their home states in the South, African-Americans had to cope with signs indicating separate entrances and separate businesses for blacks and whites, and in some towns blacks were not allowed to ride on the same streetcars with white people. Perhaps the Adams did encounter some discrimination in Seattle, but they were determined to persevere.

People in the neighborhood

We may speculate on the attitudes of neighbors, when the Adams moved into their house.

When the Adams first moved into their house at 5526 28th Ave NE, nearby lived a man from the state of Virginia, Aurelius King Shay, who had served with the Confederate Army during the Civil War. We wonder whether he ever walked along 28th Ave NE to get the streetcar at NE 55th Street and observed that a black family had moved onto the block.

Aurelius King Shay did not live in the Ravenna Orchard neighborhood for very long, however. We don’t know whether he “fled the neighborhood” because of the Adams or whether he moved in with an adult son, Julius, on Capitol Hill, because they were in business together. Failing health might also have been the reason for A.K. Shay’s move to his son’s house, because we know that Mr. Shay died of heart failure in May 1913, at age 74.

Two more of A.K. Shay’s sons, Orlando and A.K. Shay Jr., lived on 28th Ave NE about a block north of the Adams. The Shay brothers went in together to file a plat in the 5700 block, Shay’s Ravenna Addition, to sell house lots. Aurelius Jr.’s son, Alban Aurelius Shay, grew up to be a famous architect in Seattle.

Ravenna Free Methodist congregation at the Little Brown Church circa 1921, courtesy of church records.

Some people living in Ravenna Orchard were churchgoers of “progressive” churches which taught that all people are equal in value before God, regardless of race.

Rev. S.C. Benninger lived at 5559 28th Ave NE, a few doors away from the Adams, and he was pastor at the Ravenna Free Methodist Church nearby, at the corner of NE 60th Street & 33rd Ave NE. Historically, the Free Methodist church denomination had split from the main Methodist group in 1860, over the issue of slavery. The Free Methodists opposed slavery before the Civil War, and afterward Free Methodist churches were involved in setting up schools to teach freed slaves to read and write.

The Benton brothers (Hugh & Benjamin) were developers of the Ravenna Orchard blocks beginning in 1906. The Benton families lived on 29th Ave NE and showed no inclination to move away because of the Adams, nor did they stop building and selling houses in their Ravenna Orchard plat on 28th & 29th Avenues NE.

Property survey and house valuations in 1937

In the period from 1937 to 1940, the Property Tax Assessors Office of King County, including the Seattle area, did the first survey of every taxable structure. The purpose was to properly assess the value of houses and commercial buildings to assign property taxes. Like doing a census, surveyors were sent out to walk past all houses. They photographed the houses and recorded info such as the number of rooms and the general condition of the property.

For 28th Avenue NE in the Ravenna Orchard neighborhood, we don’t know if someone told the surveyor that a black family lived in the 5500 block, or if the surveyor observed this for themselves. They recorded the Adams house, and two houses on either side, with the notation that “a colored family lives in the block.” This notation was meant to indicate that the presence of a “colored family” could affect the property value of nearby houses.

The Adams’ occupations and activities

On the census of 1920 Charles Adams was listed as working at the shipyards. Neither the census nor City Directory listings gave the name of the company he worked for, but a newspaper reference indicated that it might have been Patterson-McDonald Shipbuilding at 5971 East Marginal Way.

Beginning in 1916, shipbuilding for the war effort took place at several companies located along the Duwamish Waterway in south Seattle, Georgetown area. During World War One, about 60,000 men worked in Seattle shipyards. It puzzled me that Charles Adams would choose work so far from where he lived in northeast Seattle, and I wondered how long it took him to get to work each day. On the census of 1920, including Charles Adams I counted eight men within a block of his house, who also listed themselves as employees of shipyards. For this reason, it seemed doable and perhaps some of the men traveled to work together.

In 1919, records showed that there were about 300 African-American men who belonged to the longshoremen’s union, so it appears that this kind of work was available to them, at least until after the war when the shipyards closed. The biggest shipyard, Skinner & Eddy, closed in 1921.

An activity which may have generated more income for him, was Charles Adam’s involvement in leading music programs with a “shipyard colored band.” Later in the 1920s his name appeared as leader of musical entertainment at Fourth of July programs in parks, and in 1929 there was a listing of a radio broadcast of music by Charles Adams and his “Red Hats.”

After 1921 when most of the shipyards had closed, Adam’s occupational listing in the Seattle City Directory again returned to “janitor.” He may, however, have been working for himself instead of at a company, as indicated by his classified ad in the newspaper for “Ravenna Janitor Service.” Perhaps Charles & Nora Adams worked together in cleaning services. There is at least one listing in the Seattle City Directory that Nora was a cook. Perhaps she worked for a family in the neighborhood.

Typical of people in their still-rural Ravenna Orchard neighborhood, in 1928 the Adams also raised and sold chickens & eggs.

The Adams life story

Charles Adams died in 1944 and his widow, Nora, seemed to want to stay in her house, indicating either contentment with her situation, or determination to not let anyone exclude her from the neighborhood based on her race. She continued to live in her house for about fifteen more years, alongside Eliza Driscoll who had been widowed in 1930. They were neighbors for 45 years, until Eliza’s death in 1958.

The story of Charles & Nora Adams in the Ravenna Orchard neighborhood is an American story, like that of others who came there in early years, who wanted to find an affordable place to live. Early residents like Charles Petrie were able to divide their property if they’d bought more than one lot, as a later source of income. Mr. Petrie and the Driscolls, who lived on either side of the Adams, stayed in their houses for decades. If the King County Property Tax Assessor lowered the assessed value of the Petrie & Driscoll houses due to proximity to “a colored family,” this would have been advantageous in that their property taxes would be lower!

Early residents of northeast Seattle wanted the advantages of a semi-rural environment, such as being able to keep chickens, and yet also be able to travel on the streetcar to access shopping and places of employment. The first houses on 28th & 29th Avenues NE in Ravenna Orchard were built in 1907-1908, and many still stand today. The story of Charles & Nora Adams was set in a neighborhood which provided a place for this African-American couple to find a home.

Lines of the streetcar tracks can still be seen on NE 55th Street nearest to the corner of 35th Ave NE. Calvary Cemetery is at left. Photo courtesy of Feliks Banel.

Sources:

Bryant: the neighborhood name of Bryant came into existence in 1918 when this name was given to the new wood-frame school building on NE 57th Street. In 1926 a new brick Bryant School (the present building) was constructed on NE 60th Street. Today the neighborhood is often referred to as Ravenna-Bryant.

Census and City Directory listings; newspaper search.

Census and City Directory listings; newspaper search.

Property records: Puget Sound Regional Archives, repository of the property tax records of King County. Property Tax Assessment Rolls show who owned the lots. Original photos with build dates and names of homeowners are from the 1937-1940 survey of all taxable structures in King County. See HistoryLink Essay #3692 by Paula Becker, for the story of how the survey was done.

HistoryLink Essay #9444, “1910 Census,” by John Caldbick, 2010.

HistoryLink Essay #10329, “AFM Seattle Local 493 (1918-1958) Negro Musicians Union,” by Peter Blecha, 2013. Charles Adams is not mentioned in this essay but I include it here for context of black musicians in Seattle.

James, Diana E., Shared Walls: Seattle Apartment Buildings 1900-1939, 2012. Seattle Public Library 728.31409.

“Marine Villa’s Lost Marine Hospital,” St. Louis History blog, December 5, 2014 by nicklemen, stlouishistoryblog.com

“Marine Villa’s Lost Marine Hospital,” St. Louis History blog, December 5, 2014 by nicklemen, stlouishistoryblog.com

The Marine Hospital in St. Louis, built 1850, demolished 1959, was at 3640 Marine Avenue, at the intersection of Marine & Miami Avenues, four blocks west of the Mississippi River. It was a three-story brick building in classic revival style. The neighborhood has retained the name “Marine Villa.”

“The Peopling of Seattle: Race, Migration and Integration, 1851-2015,” by Quintard Taylor. Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Winter 2015-2016, pages 24-34.

“Race Relations and the Seattle Labor Movement 1915-1929,” by Dana Frank. Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Winter 1994-1995, pages 35-44.

Seattle’s Streetcar Era: An Illustrated History 1884-1941, by Mike Bergman, 2021. Seattle Public Library 385.50979.

Seattle’s Streetcar Era: An Illustrated History 1884-1941, by Mike Bergman, 2021. Seattle Public Library 385.50979.

The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Balck and White Southerners Transformed America, by Dr. James N. Gregory, 2005. King County Library System, 304.80975.

Wilkerson, Isabel, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of American’s Great Migration, 2010, Seattle Public Library 304.80973.