By 1910 there were about 13,000 Japanese immigrants in the state of Washington. Many of these worked in lumber mills, railroad construction crews, or in agricultural work. Of that number, about 6,000 lived in Seattle.

Japanese in the City of Seattle were concentrated mainly in the Chinatown/International District which was becoming Nihonmachi (JapanTown). The Seattle Japanese were businessmen in operation of hotels, restaurants, commercial laundries, barber shops and retail establishments. The Nippon Kan Theater at 628 South Washington Street was a major cultural center and gathering place.

Historian Richard C. Berner wrote, “Japanese immigrants to Seattle played a role in the city’s development far out of proportion to their number.” In this blog article we will trace the stories of the Hara family members down three generations in Seattle.

The Hara family in Nihonmachi (JapanTown/International District)

Bunta Hara came to Seattle in 1900 and in 1913 he joined in with two other men as founders of the Grand Union Laundry at 1251 South Main Street. It became one of the largest employers in the Nihonmachi with up to seventy workers.

The Haras came to Seattle as Christians and were involved in starting the Japanese Methodist Church in 1904. It outgrew several meeting places until in 1912 they were able to build a church at 14th & Washington Streets. The church was a source of spiritual and community support, and a social network for immigrants to find jobs and housing.

Bunta & Chiyo Hara had two sons, Masayoki (James) and Iwao, who attended Garfield High School and went on to study at the University of Washington. James became a pharmacist and Iwao was an accountant. James opened his own pharmacy at 14th & Yesler Streets with his house behind it. Iwao established an accounting business which had clients from among the many businesses in the Nihonmachi.

Mutual friends introduced James to his wife Shuko Yoshihara. Both had been in the pharmacy program at the University of Washington but hadn’t met because James was five years older and had graduated ahead of Shuko. Shuko had grown up in Montana where her father was foreman of construction crews for the Northern Pacific Railway. James & Shuko married in 1937 and in 1939 they had a son, Lloyd.

James Hara at left, with college friends at the UW in 1930. Photo courtesy of Hara family collection on Densho.

The Kanazawa family were among Bunta & Chiyo Hara’s close friends at the Japanese Methodist Church. Their children, Iwao Hara and Mae Kanazawa, were married in 1939 at the Japanese Methodist Church. The couple continued to be active church members where Mae led the choir.

The shock of war news

On Sunday, December 7, 1941, Mae Hara was leading choir practice at church. They were working on The Messiah for the church’s Christmas program. Suddenly someone rushed in with news heard over the radio, that the Empire of Japan had bombed the American ships in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Choir practice was thrown into an uproar and everyone decided that they needed to go home because of the awful news. They knew immediately that there would be a declaration of war between the U.S. and Japan, and that it would bring even more persecution of Japanese-Americans. Little could Mae Hara have imagined that the next time she would lead a choir singing The Messiah, would be in an internment camp, surrounded by barbed wire in the desert of Idaho.

Later on that night of the December 7th Pearl Harbor bombing, the FBI burst into homes in the Nihonmachi and arrested numerous Japanese community leaders and owners of businesses. Shoichi Okamura, founder of the Grand Union Laundry and co-owner with Bunta Hara, was arrested.

Later on that night of the December 7th Pearl Harbor bombing, the FBI burst into homes in the Nihonmachi and arrested numerous Japanese community leaders and owners of businesses. Shoichi Okamura, founder of the Grand Union Laundry and co-owner with Bunta Hara, was arrested.

Japanese residents of Seattle were accused of possibly “colluding” with the enemy, even without any evidence of such. Mae Hara’s father Kinmatsu Kanazawa, proprietor of a wholesale fish market, was arrested and, along with others, was jailed in eastern Washington until put on trial. These heads of families were all acquitted due to lack of evidence, but they stayed in Pullman, WA, until they joined their families in the internment camp in Idaho, in 1942.

War restrictions tighten in Seattle

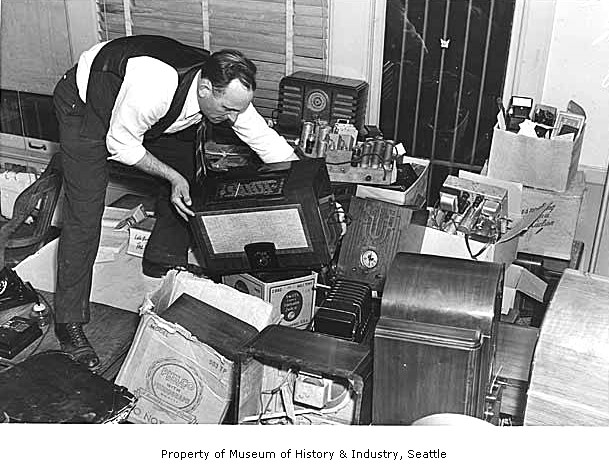

In Seattle following the Pearl Harbor attack, numerous decrees were announced due to suspicion that Japanese might be involved in helping guide the Empire of Japan into future bombing raids on the West Coast of the USA. Japanese families were required to turn in all radios and shortwave equipment as it was thought they somehow would use these to communicate with the enemy. A series of regulations increased the tightening of restrictions on what Japanese could do and where they could go in Seattle.

For a few weeks it seemed that Japanese were being urged to leave Seattle but only a few were able to do so quickly enough to get away. James & Shuko Hara were among the fortunate. James found a white man who was able to take over the Hara’s pharmacy & house at 14th & Yesler. With their two-year-old son Lloyd, James & Shuko went to Nebraska, then to Illinois. Two daughters were born to them there.

All Japanese in Seattle are sent to an internment camp

Iwao & Mae Hara delayed too long to be able to leave Seattle on their own, as James & Shuko had done. Iwao stayed because as an accountant, he felt that others were depending upon him. Then Iwao & Mae were not able to leave town because all Japanese were ordered to be under confinement and curfew in the Nihonmachi. While Iwao was still trying to plan for leaving his business, the order came that all Japanese of Seattle would be sent to an internment camp for the duration of the war.

Members of the Japanese Methodist Church requested to be sent as a group. They were sent first to the Camp Harmony “assembly center” in Puyallup to wait, and then by August 1942 they were all at the Minidoka Internment Camp in Idaho.

Before leaving Seattle, the members of the Japanese Methodist Church packed up the contents of the church and boarded up the building. They received assurance from their sister church, First Methodist in downtown Seattle, that members of First Methodist would monitor the building and keep it safe. Edward Linn Blaine of the First Methodist church was the person who made a personal vow to do this.

Youth pastor of the Japanese Methodist Church, Rev. Everett Thompson who spoke Japanese fluently, followed the group to Idaho and lived in a town near the camp. Other ministers from Seattle also followed their congregations to Minidoka and they worked together to conduct Sunday services at the camp.

Here is the description of the Christmas 1942 program at Minidoka, written in a letter (see source list):

“Over eighty-five young men and women of the Mass Choir in choir robes came down the aisle singing “O Come All Ye Faithful.” They sat in front of an improvised altar, beautiful because of a cross that hung between the folds of a draped velvet background. On the piano was a tumbleweed potted in a crepe-paper covered tin can. It was decorated with red stars. As we heard the familiar scripture reading of the First Christmas and the lovely strains by the Choir from Handel’s “Messiah,” our faith in the Prince of Peace was strengthened.”

Iwao & Mae Hara leave Minidoka

By March 1943, about a year after the evacuation order, the War Relocation Authority began to set out ways in which internees could leave Minidoka Camp. Internees could not return to the West Coast, but they could be released with proof of a job and a place to live in the Midwest or Eastern USA.

Before her marriage, Mae Hara had lived in Chicago while studying music. She wrote to the woman who had hosted Mae in her home at that time, Mrs. Rodehaver. With this assurance of a place to live and arrangements for jobs, Iwao & Mae left Minidoka in March 1943.

It was estimated that two-thirds of those in the internment camps, including Minidoka in Idaho, were born in the USA and thus were US citizens, like Iwao & Mae Hara. Mrs. Rodehaver in Chicago was part of a vast network of people who knew that Japanese-Americans were being treated unjustly. They set to work utilizing their contacts, especially for college-age Japanese-Americans to be accepted at small Christian colleges with scholarships. Back at Minidoka, Rev. Thompson was using his contacts to help the internees when there was a possibility of being released for jobs or for college.

Iwao & Mae were only in Chicago a short time until they were invited to go to Madison, Wisconsin, where Iwao was to take a job with a major accounting firm. They’d only been in Madison a few days when suddenly at their door, the minister of the local Methodist Church appeared and invited them to come and attend church services. Iwao & Mae knew that Rev. Thompson back in Idaho was working his network of contacts to make sure they received a welcome in Madison, Wisconsin.

The Hara brothers are reunited in Madison, Wisconsin

About five years after Iwao & Mae settled in Madison, Wisconsin, Iwao’s brother James & family moved there, as well. James & Shuko had lived in Nebraska and in Illinois and they now had three children, their son Lloyd who had been born in Seattle in 1939 and two girls born in Illinois.

Although James & Shuko had avoided internment, this did not mean that their lives during the war years were easy. They’d moved from place to place, experiencing racial discrimination in housing and jobs. Mae & Iwao had found less discrimination in Madison, Wisconsin, in part due to municipal support. The mayor of Madison had a German surname and knew what it was to be discriminated against due to race or ethnic origin. He directed Madison to be a place where the Japanese, arriving for jobs, were treated kindly.

To go or to stay?

The lives of the Hara brothers & their wives illustrate the tensions and difficulties experienced by Japanese immigrants and first-generation Americans. No matter what they did, they could never prove that they were “American” enough to be accepted by white people. They also had to make decisions about how much to hold onto their Japanese upbringing and culture.

The Hara brothers and their wives all had parents who remained behind in the Minidoka internment camp. I wondered if they felt any sense of obligation to stay with their parents. It surprised me, the degree to which the oldest generation, the original immigrants such as Bunta & Chiyo Hara, were willing to let the next generation go on to fulfil their own life aspirations. In research for this article, I read many stories of young professionals like Iwao Hara, whose parents urged them to take the opportunity to get out of the camp. The same was true of Mae Hara’s parents who were also at Minidoka, although some of her siblings were there, as well, so she may have been assured that they would look after the parents.

It was characteristic of the oldest generation, such as Bunta & Chiyo Hara who had come to Seattle in the early 1900s, that they wanted to return to Seattle and recreate some of the Japanese community that they had known before the war. Bunta was extremely dedicated to the Japanese Methodist Church and served many years as a leader there. Like some others who were age 60+ by the time World War Two ended in 1945, Bunta Hara’s livelihood had been destroyed and he never was able to resume work again. His generation seemed able to let their children go, to allow their children to make the best of opportunities.

Iwao & Mae Hara never wanted to return to Seattle, as they’d found jobs and opportunities in Madison, Wisconsin and were even able to buy a house. They spent the rest of their lives there. After about six years in Madison, in 1955 James & Shuko again decided to move. This time they made the decision to move back to Seattle.

Moving back to Seattle after World War Two

We may speculate on the reasons why James & Shuko Hara decided to return to Seattle in 1955. Perhaps they discussed the situation with Iwao & Mae, as to the care of their elderly parents. The Hara’s mother had died and Bunta was alone now. Soon after they returned to Seattle, James & Shuko brought Bunta Hara to live with them.

In Seattle James & Shuko found the same old discrimination in jobs and housing, but finally James got a job with a downtown pharmacy. Then the search for housing began. Shuko read the real estate listings but when she went to the office to inquire, she was always told that “it was no longer available” even though the listing continued in the newspaper after that.

During her years as a student at the University of Washington, Shuko had attended the Congregational Church in the University District. Upon her return to Seattle, she resumed attendance there and began accessing her connections. When Shuko found the house that she wanted, she found someone who would buy the house, and then the Haras rented from them. Eventually the Haras purchased the house.

Finding a house in the Wedgwood neighborhood in 1956

In 1956 the Hara family moved to 4014 NE 75th Street in the Wedgwood neighborhood in northeast Seattle. We don’t know whether it was the real estate agent, Lola Mann, who had told Shuko Hara that the house was “not available” or if it was someone else at the real estate office. Ironically, Ms. Mann had changed her surname to avoid bias, as it originally was Mannheimer, a German name.

Lola Mann in a 1935 newspaper photo when she was manager of an arts music studio in downtown Seattle.

During her career Ms. Mann had been the listing agent for houses in different areas of Seattle but in 1960, when she retired, she seemed to fall under the spell of the charming Wedgwood neighborhood. She bought her own home at 7414 45th Ave NE, about five blocks east of the Hara’s house. We may wonder if, in later years, Ms. Mann ever walked past the house at 4014 NE 75th Street and observed that a Japanese family was living there.

In the growing years of the Wedgwood neighborhood in the 1950s, houses often sold quickly, but perhaps the Hara family were able to get this one at 4014 NE 75th Street because it faced an arterial street, with the possibility of traffic noise. This was a slight disadvantage compared to the advantages of the location. The house was close by the growing commercial intersection of NE 75th Street & 35th Ave NE with a Safeway grocery and other stores. The Hara’s two daughters could walk to the nearby elementary school and to Nathan Eckstein Junior High School.

The third generation: Lloyd Hara in Seattle

In addition to caring for the elderly Bunta Hara, perhaps another reason for James & Shuko to return to Seattle was to give their son Lloyd educational advantages like what they’d had at the University of Washington in Seattle. Lloyd was about sixteen years old when the family moved back to Seattle. Lloyd attended Roosevelt High School and then went on to the University of Washington. He graduated with a degree in economics in 1962, and a Masters degree in Public Administration in 1964.

Mr. Hara stated that he went back to get the graduate degree in public affairs because he was inspired by President Kennedy’s challenge, “ask what you can do for your country.” This is an amazingly idealistic response to the challenges of citizenship, from a descendant of Japanese immigrants whose rights of citizenship were denied.

In 1969 Lloyd Hara was appointed to the office of King County Auditor, at age 30 the youngest person ever to hold that office. He was elected Seattle Treasurer in 1980, serving in that role until 1992. Other elected offices where he served were on the Port Commission and the King County Assessor’s office.

When he finally retired at age 76 in 2015, it was said that Lloyd Hara had held more local elective offices over a longer period of time than anyone in the state. He also received many awards for activism such as serving as president of the Japanese Americans Citizen League.

It’s hard to believe that just one person could accomplish so much. Lloyd Hara’s life demonstrated the saying that Japanese citizens gave benefit to the City of Seattle far beyond their numbers.

Sources:

Blaine Memorial United Methodist Church, 3001 24th Ave South, Seattle, 98144. blaineonline.org

Blaine Memorial United Methodist Church, 3001 24th Ave South, Seattle, 98144. blaineonline.org

Summary history of the church which began as the Japanese Methodist Church in 1904. Members of First Methodist in downtown Seattle helped in the formation of this church, including Mr. E.L. Blaine. Mr. Blaine and others faithfully protected the Japanese Methodist church building while it was closed during World War Two. The church started up again after the war and renamed itself Blaine Memorial in 1956. In 1962 they moved to their present address on Beacon Hill.

Edward Linn Blaine, Sr. (1862-1954) Biography on Find A Grave. He was the second son of Rev. David & Catherine Blaine, the first Methodist church workers in Seattle. Mr. Blaine was a long-time member of downtown Seattle’s First Methodist Church. Mr. Blaine gave his word to protect the Japanese Methodist Church building during World War Two. In 1956 the church renamed themselves in his honor, Blaine Memorial Methodist Church.

Densho website – recorded interviews with Mae Kanazawa Hara.

Japanese in Seattle and King County:

This blog article about the Hara family is meant to include only information about Japanese who had lived in Nihonmachi, the business district of the Chinatown-International District, where first-generation Japanese immigrants operated businesses such as hotels.

Many other Japanese lived in rural King County and did agricultural work. Up until the forced evacuation of early 1942, seventy-five percent of Pike Place Market farmers were Japanese sellers of fruit, vegetables and flowers. Many never returned to the Market after the war.

An art installation called Song of the Earth, a mural honoring Japanese immigrants, is located at the entrance below the Public Market center clock and sign. The panels of the mural portray logging, farming, selling produce and viewing Mt. Rainier. The artwork by Aki Sogabe was completed in 1998.

In north Seattle (north of the ship canal) there were some small farms such as at Sand Point, at the present site of University Village shopping center and at the present freeway through Northgate. Other Japanese in north Seattle operated dry cleaners and fruit stands and did landscaping work. Other articles on this blog are: The Fukano family in Fremont; the Akahoshis who lived at the present site of Dahl Field; and the Nishitani’s Oriental Gardens plant nursery at NE 98th Street and Lake City Way NE.

Sources (continued):

“Letter to Miss Alice W. S. Brimson from Shigoko Soso Uno, 11 January 1943.” Box 1/Folder 3, Emery E. Andrews Papers, UW Library, Seattle. Excerpt about the Christmas 1942 program at the Minidoka camp.

Minidoka National Historic Site – minidoka.org

National Archives: Compensation and Reparations for the Evacuation, Relocation and Internment Index. http://www.archives.gov/research/japanese-americans/redress. In 1988 under President Reagan, legislation was passed to compensate each still-surviving person who had been in an internment camp.

Nippon Kan theater, built 1909 at 628 South Washington Street. Photo by Asahel Curtis in 1911, courtesy of Washington State Historical Society.

“1910 Census,” HistoryLink Essay #9444 by John Caldbick, 2010.

“Nippon Kan Theater (Japanese Hall) opens in 1909,” HistoryLink Essay #3180 by Priscilla Long, 2001.

Nisei Daughter by Monica Sone, 1953. Seattle Public Library, biographies. The 2014 edition of the book has a new introduction and preface and includes the preface to the 1979 edition.

“Panama Hotel opens in Seattle’s Japantown in the summer of 1910,” HistoryLink Essay #9544, by Colleen E. O’Connor, 2010.

“Seattle 1900-1920,” Seattle in the 20th Century, Volume 1, 1991, by Richard C. Berner. Pages 66-69, Seattle’s Japanese Community.

“Shoichi Okamura founds the Grand Union Laundry in 1913,” HistoryLink Essay #3181 by staff, 2001.

Shuko Hara obituary of 2018, Legacy.com

“World War Two Internment of Japanese-Americans in Washington,” HistoryLink Essay #22995 by Eleanor Boba, 2024.

What an amazing saga! Thanks for all the research you do!!

Thank you for putting this together! I knew who Lloyd Hara was, of course, and certainly about the wartime internment, but never knew his backstory, or that there was a connection to Wedgwood. 👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼

Praise and thanks to the anonymous “ally” of the Hara’s mentioned in the statement: “When Shuko found the house that she wanted, she found someone who would buy the house, and then the Haras rented from them. Eventually the Haras purchased the house.” May we all have the insight and wisdom to be allies in our own day and age. The movement towards racial equity is far from completed.